Since I haven't made an update in a few months now, I'll preface this article with a brief recap of my doings and musings over the past two days. Indeed, this was a good weekend for medievalists, worthy of reflecting. Saturday was the feast of saints Crispin and Crispinian, two ancient Roman martyrs whose following became quite popular in later medieval England. The patron saints of cobblers, this feast was a major public holiday for everyone involved in the tanning and leathermaking industry. On the fateful morning of October 25, 1415, the hopelessly outnumbered and exhausted state of King Henry V of England's invading army prompted the Earl of Westmoreland to exclaim, "O, that we now had here but one ten thousand of those men in England that do no work today!" And the rest is "history", of course.

As per tradition every year, I dutifully watch the Kenneth Branagh adaptation of Shakespeare's Henry V and cry "God for Harry, England, and Saint George!" Every year, a French historian or two objects to the celebrating of war crimes or grossly exaggerated kill counts across the Channel, and then an English historian says nay, 'twas not so, we really did slay over nine thousand Frenchies with ten archers and a cheese knife. Saints Crispin and Crispinian themselves invariably get lost in the festivities, so this time, I share with you the following link, proposing the two martyrs as patron saints of catechists.

A good friend of many years, Theodore of the Royalty & Monarchy Site, invited me to travel up to Dallas to attend a concert given by the Choir of Westminster Abbey on Sunday the 26th, which happened to be passing through the Episcopal church where he sings during their tour of the United States. Yes, the same choir that sings at the burial place and coronation site of the kings of England since 1065. The same choir that millions of folks otherwise oblivious to all this stuff heard while watching the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton, now the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. And the same choir that my fiancée and I heard when we visited the Abbey for choral Evensong on Christmas Day of 2011 (we were checking up on stolen property). Theodore probably didn't expect me so willing to attend as to bring the entire family for the ride, but I did, and though it was quite a hectic trip to and fro (six hours each way) with very little time to stop and relax, it was certainly worth it.

Sunday morning began with a visit to the church of Mater Dei, Irving. Though I have numerous friends who are or were seminarians of the Priestly Fraternity of Saint Peter, and have attended Masses celebrated by FSSP priests before, this was the first time I ever actually visited one of their churches. Sung Mass began at 9 in the morning, which despite being the most traditional time to celebrate it (following the divine hour of Terce), is always a maddening proposition for us not-morning folk. It was the feast of Christ the King, which is always on the last Sunday of October in the 1962 calendar and, despite the feast's recent coinage, gave heightened significance to Saturday's royal victory and that afternoon's equally royal entourage. There was a rather lengthy homily on the recent synod on the family in Rome given by Father Wolfe, who I briefly met during a visit to the ill-fated Fisher-More College in Fort Worth a couple years ago. If some homilies are like cotton candy and others are like meat and potatoes, this one was rather like eating a brick that chipped my tooth. Father Hunwicke this, Pope Honorius that, but it seemed to give solace to my fiancée who was entertaining thoughts of converting to Eastern Orthodoxy after the fiasco of the midterm report. After Mass, there was a Eucharistic procession in honor of Christ the King around the parking lot, Benediction, and multiplication of the doughnuts and muffins. The people were friendly, and a few even conversed with me and Lauren. An unfortunate ad for Rick Santorum on a bulletin board in the narthex, and an even more unfortunate painting of the Sacred Heart, detracted from an otherwise edifying experience.

|

| Folks filing back in to Mater Dei after the procession. They did the best they could with this old Korean Presbyterian church building. |

After Mater Dei, it was lunch with Theodore, where he, Lauren, and I talked at length about choral music and other matters of import, and then on to the purpose of the trip: to listen to the Westminster Abbey Choir in concert. One thing can be said for the people who built the Episcopal Church in America: they were not stingy in giving. The Church of the Incarnation, from nave to parish hall, was a lot nicer than what I'm used to in an ordinary parish church. Now, I must concur with Lauren, who remarked that the surroundings felt devoid of the presence of God that we feel when inside a Catholic church, but that's another story for another time. Yesterday, I was a guest, supporting an institution I'm quite fond of: the traditional choir of men and boys.

The repertory was mostly of large texts by 19th and 20th century composers that I didn't know much about, but it began with "Hosanna to the Son of David" by Orlando Gibbons, then two responsories by Thomas Tallis (Videte miraculum from Candlemas, and Loquebantur from First Vespers of Pentecost). There was a huge choral work set to three prayers by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a Lutheran minister who earned death in a concentration camp for his opposition to the Nazi Party. My favorite of all the texts that I had not heard of before was this bit called "The Twelve" by Wystan Hugh Auden, set to music by William Walton (this sample courtesy of the Choir of King's College, Cambridge):

I

Without arms or charm of culture,

Persons of no importance

From an unimportant Province,

They did as the Spirit bid,

Went forth into a joyless world

Of swords and rhetoric

To bring it joy.

When they heard the Word, some demurred, some mocked, some were shocked: but many were stirred and the Word spread. Lives long dead were quickened to life; the sick were healed by the Truth revealed; released into peace from the gin of old sin, men forgot themselves in the glory of the story told by the Twelve.

Then the Dark Lord, adored by this world, perceived the threat of the Light to his might. From his throne he spoke to his own. The loud crowd, the sedate engines of State, were moved by his will to kill. It was done. One by one, they were caught, tortured, and slain.

II

O Lord, my God,

Though I forsake thee

Forsake me not,

But guide me as I walk

Through the valley of mistrust,

And let the cry of my disbelieving absence

Come unto thee,

Thou who declared unto Moses:

"I shall be there."

III

Children play about the ancestral graves, for the dead no longer walk.

Excellent still in their splendour are the antique statues: but can do neither good nor evil.

Beautiful still are the starry heavens: but our fate is not written there.

Holy still is speech, but there is no sacred tongue: the Truth may be told in all.

Twelve as the winds and the months are those who taught us these things: envisaging each in an oval glory, let us praise them all with a merry noise.

(Quite metal, when you think about it.)

|

| The choir stalls at the (Episcopal) church of the Incarnation in Dallas, where the concert was held. Unlike in American Catholic-dom, choir stalls seem omnipresent in Episcopal-land. |

First, they fulfill a function in the Catholic tradition that women simply cannot. Before you jump up and say, "hey, I/my wife/sister/daughter/mother is in church choir" and send me a hatemail, let me be clear: yes, the Church has allowed female altar servers for decades in the modern form of the Mass, and women in lay choirs for over a century; and it's true, there's nothing inherently wrong with women in lay choirs (in civilian dress, typically singing from a loft or otherwise hidden from the public gaze). I'd be happy for all my daughters to join a lay choir when they come of age. A lay choir is nothing more than a specialized subset of the faithful at large, and if the faithful are encouraged to sing the Ordinary of the Mass, as they did in ancient times, there can't be anything wrong with a specialized subset (naturally including women) doing the same thing. There are women in lay choirs in every church I sing at, so if I had a problem with them outright, I guess I'd be shown the door sooner or later.

But as choirs go, the traditional Latin Mass's rubrics only concern themselves with one: the liturgical or ecclesiastical choir*, assumed (just as with altar servers) to all be clerics in cassock and surplice, seated in choir stalls in the sanctuary (or quire, or chancel), the gospel and epistle sides facing one another. And naturally, as women cannot be clerics in the Catholic Church, those who populated the choir were all male. These men and boys alone were expected to sing the five proper chants; Introit, Gradual, Alleuia (or Tract in Lent), Offertory, and Communion; which change every day. For years, our men's schola had to juggle learning five all-new, melismatic chants virtually every Sunday, only to put them away for the entire year until that Sunday occurred again, while also maintaining jobs, children, schooling, or some combination of the above. Sung Masses aren't quite as frequent at the diocesan 1962 Mass here this year, but even so, if our schola wasn't there, there wouldn't be any chant at all.

In the medieval world, on the other hand, this task was generally left to boys and men who dedicated their entire lives to the sacred art of chant: clerks ordained to the minor orders at the parish level (perhaps permanently), monks in their monasteries, students in their college chapels, and canons in their cathedrals. No priest was exempt from the duty to sing. Today we have the expression, "I asked my priest to say Mass for my sick cat yesterday", but in the Middle Ages, you were more like to say that a priest sang Mass for such-and-such an intention, such as not dying from plague or shipwreck. Hence, in Shakespeare's play, on the eve of Saint Crispin's, Henry V gets on his knees and prays for pardon for his father having usurped the crown from Richard II:

O God of battles! steel my soldiers' hearts;

Possess them not with fear; take from them now

The sense of reckoning, if the opposed numbers

Pluck their hearts from them. Not to-day, O Lord,

O, not to-day, think not upon the fault

My father made in compassing the crown!

I Richard's body have interred anew;

And on it have bestow'd more contrite tears

Than from it issued forced drops of blood:

Five hundred poor I have in yearly pay,

Who twice a-day their wither'd hands hold up

Toward heaven, to pardon blood; and I have built

Two chantries, where the sad and solemn priests

Sing still for Richard's soul. More will I do;

Two chantries, where the sad and solemn priests

Sing still for Richard's soul. More will I do;

Though all that I can do is nothing worth,

Since that my penitence comes after all,

Imploring pardon.

But why boys, you ask? For American Catholics, the answer is easy. "Start 'em young." We Americans have long been used to the idea of the "altar boy", encouraging them from the time they can take directions to serve the altar in the hope of fostering another vocation to the priesthood. Unfortunately, we also have historically tended to throw them right into low Mass where the server assumes many of the duties of the deacon and subdeacon, but the average boy can only learn so many directions and Latin phrases at a time, so we have also gotten accustomed to the fatal double-whammy of 1.) sloppy serving, and 2.) thinking older teenagers and adult men are too old to serve, thus forbidding the problem from ever being solved.

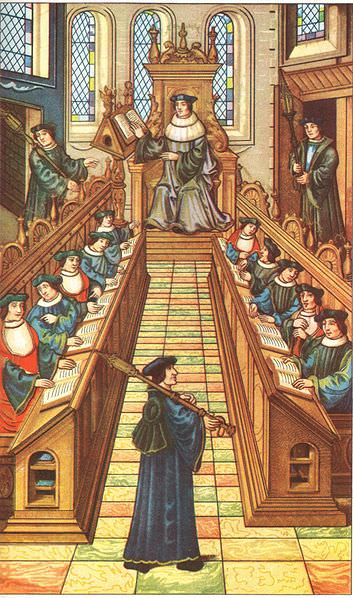

Medieval Christendom had another model: yes, boys served Mass (and even played at being bishop from time to time), but they started with minor positions at solemn Masses such as torchbearing before tackling low Mass, in the unlikely event that they did so at all. But even before boys carried torches, they had to learn how to simply sit in choir and sing the Mass. In those days, singing the entire liturgy from cover to cover was still the norm, and it remains true today that singing is a skill best cultivated from an early age. At the turn of the second millennium, the western Church's bases of influence gradually shifted from the monasteries (those fortresses and repositories of knowledge in a more brutish era) to the bishops and their cathedrals. Everywhere, bishops raced to raise up the tallest tower, the largest nave, the grandest stained-glass windows. But what was the point of developing Gothic architecture, spending millions, and putting thousands of laborers to work on a building that would be empty most of the time? No; the cathedrals of the Gothic age would have the divine hours sung round the clock by the bishop's canons. And who would assist and eventually replace them in their holy duties? The boys of the cathedral school.

Here stood the predecessor of the Tridentine seminary system. Before there were seminaries, Charlemagne ruled that cathedrals in his empire establish schools so that boys may learn to read, write, sing, and go on to serve as the next generation of clergy. The boys sang the daily Masses and Office, and the better they sang, the further the bishop grew in prestige, and the more likely the great nobles of the realm would send their sons to the schools. From these early foundations sprung the first colleges, and the universities of Bologna, Paris, Oxford, and Cambridge. It was also these boys who, together with the men, developed the additional voices to the plainchant which led to polyphony. By the 15th century, polyphonic settings of the Mass were everywhere, and as there were still neither women nor castrati in church choirs of any sort, the treble voices for all these compositions necessarily had to be sung by boys.

The Catholic Church in America has never had a strong tradition of choral music, but now there's a crisis of bad music throughout the entire Catholic world. This was readily apparent when the Westminster Abbey Choir visited Pope Benedict a few years ago and sang Palestrina with the Sistine Chapel Choir, making the Italians look like amateurs and prima donnas at their own game, in their own house. What's worse: the art of singing itself has been resigned, in many Catholics' eyes, to a feminine activity. "My boys serve, my girls sing;" as though there were a great distinction between the two! Thus, if I were to ask someone if they were interested in joining our schola, the answer 90% of the time will be, "I can't sing". Perhaps if they had started learning when they were eight years old, it would be another story. And now we have a problem of many generations of churchmen in America and elsewhere who can't sing, never grew up in a singing environment, and therefore, sing very little or none of the liturgy during their entire priestly careers. All of a sudden, a great tradition of sung liturgy is as dead as the public Divine Office, save for the Eastern rites and a few pockets of sanity here and there. Imagine how different our musical culture would be if every cathedral, if every parish, had a dedicated program for training boys to sing daily services, assisted by a sizable contingent of adult male scholars.

It's my general experience that when it comes to Church matters, women tend to be much more willing to volunteer, even if they're juggling multiple young children. They'll do whatever they're asked, behind the scenes, without reward or recognition. Men need to be led by example, to be seen and recognized for their service. Certainly less noble, and yet, there's the paradox that no matter how intensely religious a mother is, if a father is inactive in his faith, their beliefs are unlikely to be passed on to the children when they come of age.

Therefore, I propose an experiment for all churchmen and altar guild leaders who recognize the problems in our musical culture:

1.) Let traditional choir stalls, or at least a few movable seats, be placed within the sanctuary of every parish (for those with rails and claustrophobic sanctuary spaces, this may necessitate moving them forward).

2.) Since altar guilds usually have many more servers on the roster than can actually serve on any given Sunday, let all those who are not scheduled to serve a specific position be assigned to sit in choir. This way, new servers can witness the ceremonies of the liturgy up close before taking them up themselves, and so that they can also lead the laity in the proper sitting, standing, or kneeling postures, rather than the confusion that abounds in so many places I've attended (true that in the traditional Latin Mass, there are no rubrics for the laity, but I've seen people awkwardly split between standing and kneeling after the Canon, for example, for lack of direction rather than strict personal preference).

3.) Let all the male singers of the choir also don the cassock and surplice, properly called "choir dress", and take places in the sanctuary, leading all the other servers in choir to sing the Mass; at least the Ordinary chants (Kyrie, Gloria, etc.) whenever they are sung in plainchant. If you place boys in altar service with the hope of raising vocations, they'll need to know how to read square notation as much as the prayers at the foot of the altar.

4.) By starting to train boys to sing at a young age, hopefully as they grow into adults, the community will always have trained chanters ready to step in and lead the chants of the Mass, rather than work the same three or four dedicated chanters one Sunday after the other!

I'm just pontificating from my proverbial armchair here, but it seems like this model, as it was practiced in the great cathedrals of the medieval world, would go a ways toward restoring liturgy worldwide to its ideal, normatively sung form.

_________________________

*The liturgical or ecclesiastical choir was defined as such by Pope Pius X in his 1903 motu proprio on sacred music, Tra le sollecitudini:

"With the exception of the melodies proper to the celebrant at the altar and to the ministers, which must be always sung in Gregorian Chant, and without accompaniment of the organ, all the rest of the liturgical chant belongs to the choir of levites, and, therefore, singers in the church, even when they are laymen, are really taking the place of the ecclesiastical choir. Hence the music rendered by them must, at least for the greater part, retain the character of choral music." And, "On the same principle it follows that singers in church have a real liturgical office, and that therefore women, being incapable of exercising such office, cannot be admitted to form part of the choir. Whenever, then, it is desired to employ the acute voices of sopranos and contraltos, these parts must be taken by boys, according to the most ancient usage of the Church."

_________________________

*The liturgical or ecclesiastical choir was defined as such by Pope Pius X in his 1903 motu proprio on sacred music, Tra le sollecitudini:

"With the exception of the melodies proper to the celebrant at the altar and to the ministers, which must be always sung in Gregorian Chant, and without accompaniment of the organ, all the rest of the liturgical chant belongs to the choir of levites, and, therefore, singers in the church, even when they are laymen, are really taking the place of the ecclesiastical choir. Hence the music rendered by them must, at least for the greater part, retain the character of choral music." And, "On the same principle it follows that singers in church have a real liturgical office, and that therefore women, being incapable of exercising such office, cannot be admitted to form part of the choir. Whenever, then, it is desired to employ the acute voices of sopranos and contraltos, these parts must be taken by boys, according to the most ancient usage of the Church."

|

| The facial expression here has a certain semblance to Lady Mary Crawley's. |

|

| The front door, the great threshold for the unchurched seeker: an important but oft-overlooked place to for a church to put in its finest craftsmanship. |

|

| During the reception. Thanks again, Theodore. |

.jpg)