|

| A Sarum Missal, dated around 1418. A mention of the Pope in the far right column has been scratched out by order of Henry VIII. |

In case you've missed previous articles, please check those out first:

-

The Use of Sarum: A Brief History, and Why It Matters

-

The Sarum Low Mass: Mass of the Catechumens

-

The Sarum Low Mass: Mass of the Faithful

If you've been following my series in the Sarum Use, we've so far covered its general history and what a spoken, or low Mass would have looked like in most of England before the Reformation. Low Mass is useful for seeing the substance of the liturgy, but the rubrics presume that high Mass is the norm. We saw how the Sarum low Mass appears to have been only a slight variation of the Roman Mass with a few medieval "accretions" here and there. The high Mass will show the pageantry of the medieval spirit in full.

High Mass is defined here as Mass sung with a deacon and subdeacon. In the Middle Ages, there was no such thing as a missa cantata with a priest and servers only. The rubrics as explained by Pearson's The Sarum Missal Done into English seem to have been intended for the cathedral of Salisbury itself; it presumes an abundance of canons and a very spacious church. I believe it's safe to say that the parishes modified these rubrics liberally to suit their resources.

The Sunday Procession and Aspersion

In our Tridentine form of the Mass, the "principal" Mass of a church on Sunday is supposed to be preceded by an aspersion: the priest, vested in cope, goes down the nave sprinkling the people with holy water as Asperges Me is sung. Its counterpart in Sarum is nearly a service in itself. (though unlike Trent, this rite in Sarum is omitted if a double feast falls on a Sunday.)

These directions are taken from the

Sarum Processional. The priest, "after Prime and Chapter", is at the step of the quire (or, we could say, at the sanctuary gate) in alb and cope. The deacon and subdeacon are with him, holding his book. There are also a thurifer, crucifer, and acolytes, all wearing albs and amices (the Tridentine form prescribes only surplices for anyone not one of the three sacred ministers). Finally, there are "the boys with salt and water and the Book, who are in surplices". It's possible that these very junior positions of service were allowed to boys, while the higher serving positions had to be filled by men or older boys ordained to the minor orders.

Before starting with Asperges Me, Sarum has the celebrant bless the holy water. I believe these prayers are also in the Tridentine books. I'll provide only the English translation of this portion for now. He first exorcises the salt:

I exorcise thee, O creature of salt, by the living God, + by the true God, + by the holy God, + by the God Who commanded thee to be cast into the water by Elias the prophet, that the barrenness of the same might be healed, that thou become salt for the preservation of them that believe, and be to all who take thee salvation of soul and body; and from the place wherein thou shalt be sprinkled let every delusion and wickedness of the Devil and all unclean spirits, when adjured, fly and depart, by Him; Who shall come to judge the quick and the dead, and the world by fire.

Amen.

Let us pray. We humbly implore Thy boundless loving-kindness, Almighty and everlasting God, that of Thy bounty Thou wouldst deign to ble+ss and sanc+tify this creature of salt, which Thou hast given for the use of mankind; let it be unto all who take it healthy of mind and body; that whatsoever shall be touched or sprinkled with it be freed from all manner of uncleanness, and from all assaults of spiritual wickedness. Through Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Then the exorcism of water:

I exorcise thee, O creature of water, in the Name of God + the Father Almighty; and in the Name of Jesus Christ, + His son, our Lord; and in the power of the Holy + Ghost; that thou mayest become water exorcised for the chasing away of all the power of the enemy; that thou mayest have strength to cast out the enemy himself and his apostate angels, by the power of the same, our Lord Jesus Christ, Who shall come to judge the quick and the dead, and the world by fire.

Amen.

Let us pray. O God, Who for the salvation of mankind hast hidden one of Thy greatest sacraments in the element of water, graciously give ear when we call upon Thee, and pour upon this element, prepared for divers purifications, the power of Thy blessing; let Thy creature serve in Thy Mysteries, by Divine grace be effectual for casting out devils and for driving away diseases, that on whatsoever in the houses or places of the faithful this water shall be sprinkled, it may be freed from all uncleanness, and delivered from hurt. Let not the blast of pestilence nor disease remain there; let every enemy that lieth in wait depart; if there be ought which hath ill-will to the safety and quietness of the inhabitants, let it flee away at the sprinkling of this water, that they being saved by the invocation of Thy Holy Name, may be defended from all that rise up against them. Through Christ our Lord.

Amen.

The rubric then says "Here let the Priest cast salt into the water in the form of a Cross, saying":

Let this become a mixture of salt and water, in the Name of the Father, + and of the Son, + and of the Holy Ghost. + Amen.

V. The Lord be with you.

R. And with thy spirit.

And this last prayer before the sprinkling really caught my attention. Read it carefully:

Let us pray.

O God, Author of invincible might, King of a dominion which cannot be moved and ever a Conqueror, Who puttest down the strength of all that rise up against Thee, overcomest the rage of the adversary, and by Thy power dost cast down his wickedness; we, O Lord, with fear, humbly entreat and implore Thee mercifully to look upon this creature of salt and water; after Thy loving-kindness graciously illumine and sanctify + it, that wheresoever it shall be sprinkled, by the invocation of Thy holy Name all unclean spirits which lie in wait may be cast out, and the dread of the serpent be chased far away; and let the presence of the Holy Ghost vouchsafe to be with us who ask Thy mercy in every place. Through Christ our Lord.

Amen.

I don't know if that prayer originated in Rome, Normandy, or England first, but it beautifully captures the best of the Gothic spirit. Here, God described as the God of Battles, as in the days of the Old Testament. War, plague, famine, and death were everyday realities for those who attended the Sarum Mass, just as they were for the ancient Israelites. Yet we also see here that, contrary to the stereotypes of medieval religion as being totally distant from the hearts of the everyday peasant, God has a direct, earthy presence in the lives of the people. The priest asks Him to empower the everyday substances of salt and water ("this creature", it says) with His love so that whoever uses that holy water may count upon the name of Jesus as a surefire ward against the defilement of evil spirits. Superstitious? The Protestant Reformers certainly thought so, but I see a spirituality that uses everyday items to bring faith to a people who had neither the ability nor the inclination to read a book. Furthermore, it reflects the spirit of the Gothic age, which achieved a perfect balance in emphasizing God as both warrior and peacemaker: not too mushy, and not too distant.

After that collect, the celebrant sprinkles the altar, then his assistants, then the choir: first the north side, then the south, while Asperges Me is sung (or Vidi Aquam from Easter to Trinity Sunday). He then exits the chancel in procession via the north entrance (remember, these rubrics assume sanctuaries are enclosed, elongated spaces with three points of entry), turns right, and begins sprinkling the side altars in all the chapels around the east end of the church.

The procession according to Chambers in Divine Worship in England in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, is arranged as such: first, a beadle, clearing the way with a mace or staff in hand. A beadle, by the way, is a lay official who acts as a bodyguard and keeper of the peace. (The name comes from an Anglo-Saxon word, bydel, meaning "to bid". The beadle does his master's bidding.) Our modern counterpart is the usher, though our ushers rarely have ceremonial significance now. The only time I've ever seen a beadle in modern Catholic practice is photos of ceremonies by the Institute of Christ the King in Europe, typically involving Cardinal Burke. Other Sarum sources call him a verger, which means nearly the same thing. He carries a rod called a virge, or virga.

|

| Illustration from the Sarum Procession showing who stands where. |

After the beadle/verger follow the asperger (boy in surplice carrying the holy water), the crucifer with the processional cross (only on double feasts or higher), two cerofers (candlebearers) side by side, thurifer, subdeacon, deacon, and celebrant. Interestingly, there's never any mention of a master of ceremonies, which leads me to wonder if that position is of more recent vintage. (It's possible to omit the MC in the Tridentine high Mass if everyone knows exactly what they're doing, but the MC is still a standard practice at every Tridentine high Mass I've ever been to.)

The procession, after sprinkling all the side altars, goes up the nave to sprinkle the people. I've also seen several sources state that the procession went to every side altar in the church to incense them, but I haven't seen a specific rubric for it, nor do I see how the priest could use the holy water and the incenser at the same time unless, perhaps, one or the other is delegated to the deacon. In any case, when the procession returns to the chancel, they stop underneath the rood, and the priest sings the versicle Ostende nobis, followed by the prayer Exaudi nos, Domine, just as in the 1962 Missal.

The rubrics next have the bidding prayers (like the intercessions of the faithful in the Novus Ordo Mass) are prayed in the common tongue, but for whatever reason, only in the cathedral. The practice for the parishes is to have the bidding prayers later in the Mass, so that's where I'll explain them.

The Beginning of Mass: the Office (Introit), Kyrie, Gloria

After the aspersion rite, the ministers retreat to the sacristy to vest for Mass "whilst the Choir is saying Terce". For the smaller parishes that didn't have sacristies in the first place, it's likely that the vesting and preparatory prayers were made before the altar.

The Mass vestments are the same as we know them today, except that the acolyte who bears the processional cross is allowed to wear a "mantle", which is supposed to be like the subdeacon's tunicle, just shorter or less apparelled. The other servers, aside from the boys who are allowed to go in merely surplice, still wear alb and amice. Meanwhile, the two cantors of the choir, who were presumed to be priests and canons, also put on copes and bear staves symbolizing their office, thence becoming "rulers" of the choir. It's also said that in those days, the directors of choirs actually slammed the staves onto the floor to measure time in figured music; a practice which would no doubt be completely obnoxious to see and hear today. On double feasts, we would see four rulers! The rulers were certainly envisioned for cathedral practice and ignored in parishes that couldn't provide them.

The choir, already in place in the chancel, begins singing the Office, as Sarum calls the Introit, the rulers intoning the first words. On Sundays and feasts, the Office is supposed to be sung three times rather than just two: the antiphon, verse, antiphon, doxology, then antiphon again. At hearing the words Gloria Patri, the ministers line up to process back to the altar. The order, again according to Chambers, is: (crucifer), two cerofers, thurifer, subdeacon carrying the Gospel-book, deacon carrying the Missal, and celebrant.

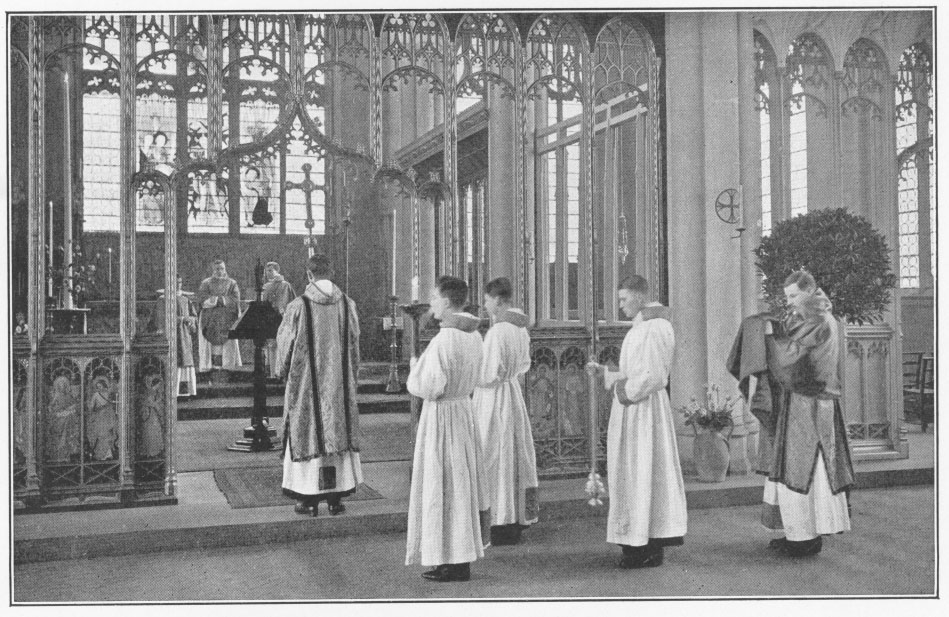

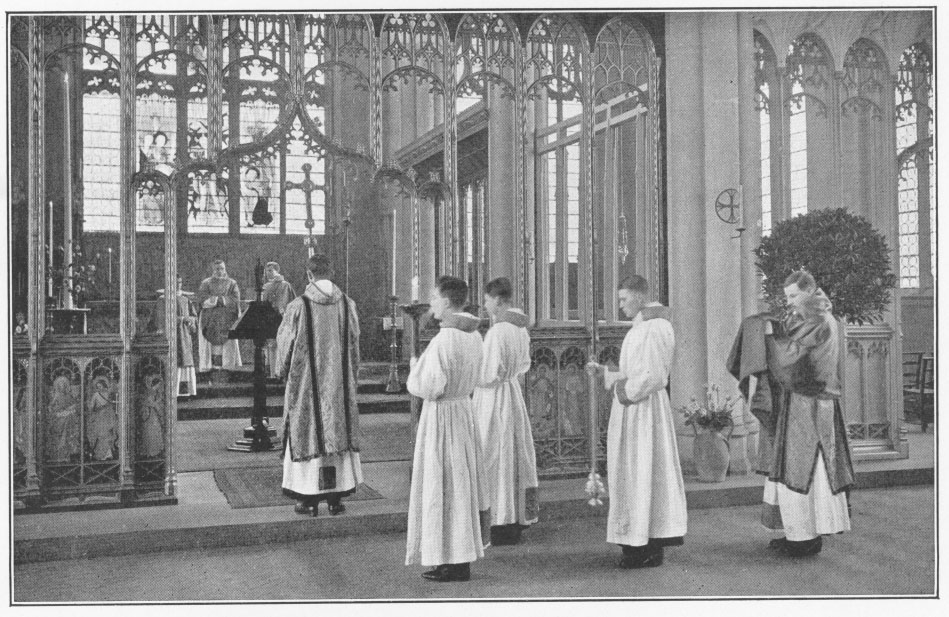

|

| These pictures are from an old publication by the Alcuin Club, an Anglo-Catholic organization. The man in black to the right is the beadle/verger. Bear in mind that these are actually photos of the Anglican Prayer-book Communion service, dressed to resemble the Sarum Mass as much as possible. |

The ministers stop at the foot to recite the last words of the Lord's Prayer, then the veriscle Confitemini Domino and response, then the Confiteor. After the absolution, the celebrant gives a kiss of peace to the deacon, then to the subdeacon. This peace is brief and given to no one else, but it's also prescribed for every day of the year, save for the three days before Easter.

The celebrant ascends the altar, prays Aufer a nobis, then kisses the altar and makes the sign of the cross with In Nomine Patris. He is then given the thurible by the deacon, who says:

Deacon. Benedicite.

Celebrant. Dominus. Ab ipso benedicatur hoc incensum in cujus honore

cremabitur. In Nomine Patris, etc.

|

D. Bid a blessing.

C. The Lord, in

Whose honour this incense shall be burnt, by Him be it blessed. In the Name

of the Father, etc.

|

He incenses the right side, then the middle, then the left. He then returns the thurible to the deacon, who incenses him before returning it to the thurifer. The subdeacon presents the Gospel-book for the celebrant to kiss. Meanwhile, the cerofers have placed their candles at the foot of the altar; perhaps atop two tall stands on either side of the foot.

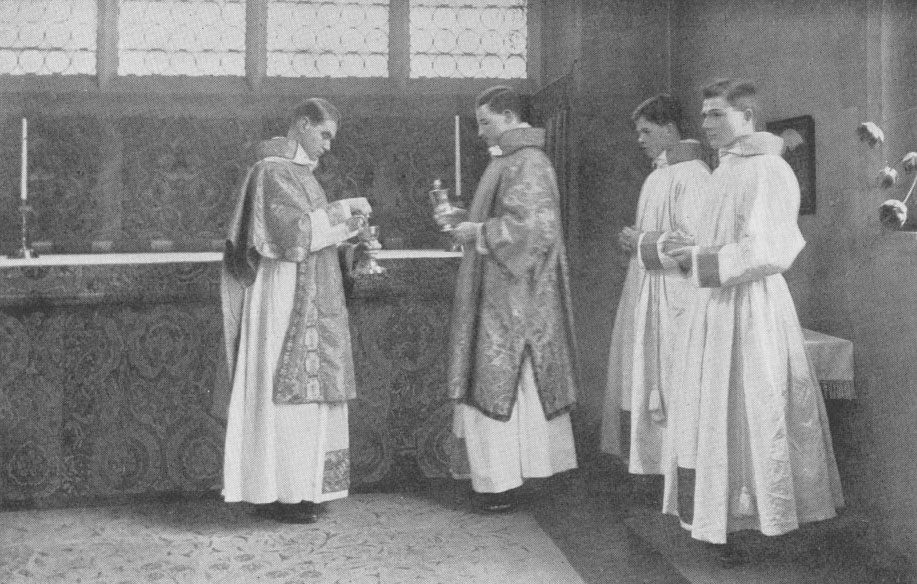

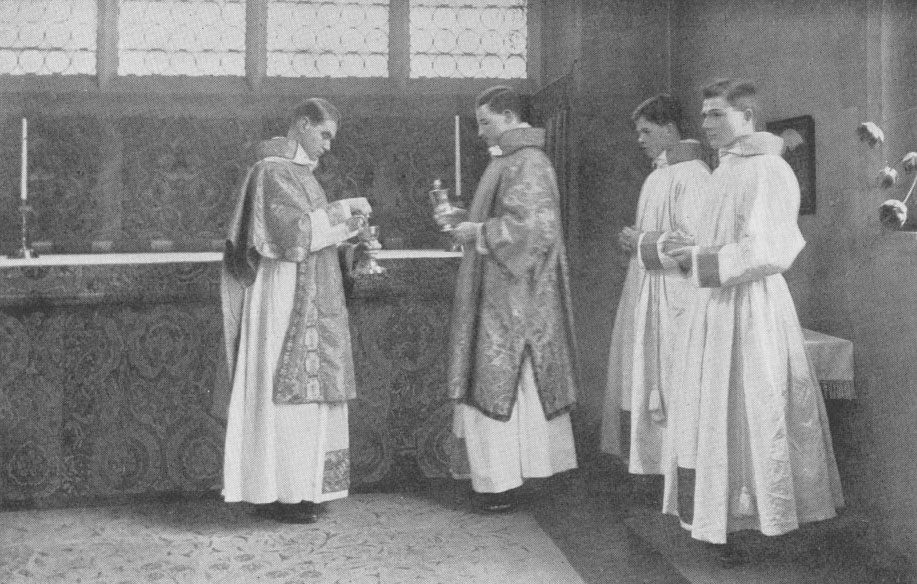

|

| The thurifer hands the thurible to the deacon. It appears the subdeacon is removing the Missal from the altar, which is resting on a cushion rather than a stand. |

While the celebrant goes on privately reciting the Office and Kyrie at the Epistle side of the altar, the choir has been singing the Office and probably gone on to chant the Kyrie by now. On many days, the Kyrie is "farced" or has tropes, so in these cases, it's likely that the ministers will have time to sit at the sedilia even before starting the Gloria.

The cerofers, meanwhile, depart after the celebrant has read the Office. They go to the sacristy to fetch the gifts. One brings the cruets of wine and water, as well as the pyx with the bread; the other carries the ewer and towel for the hand-washing. Both return to the sanctuary and place these "on the shelf over the piscina". Medieval churches typically had these built into the wall, east of the celebrant's seat in the sedilia. In the absence of these, we can take it to mean the credence table, though Sarum assumes the presence of the credence as a distinct piece of furniture. The cerofers then take up their candles and meet the mantled/tunicled acolyte, who has brought the chalice, paten, and burse, all covered in a veil. The acolyte provides a further degree of protection by carrying them in the humeral veil. After setting the chalice down on the credence, he removes the two corporals from the burse (or corporal and pall) and lays them on the altar, kissing it afterward. He then returns to the credence.

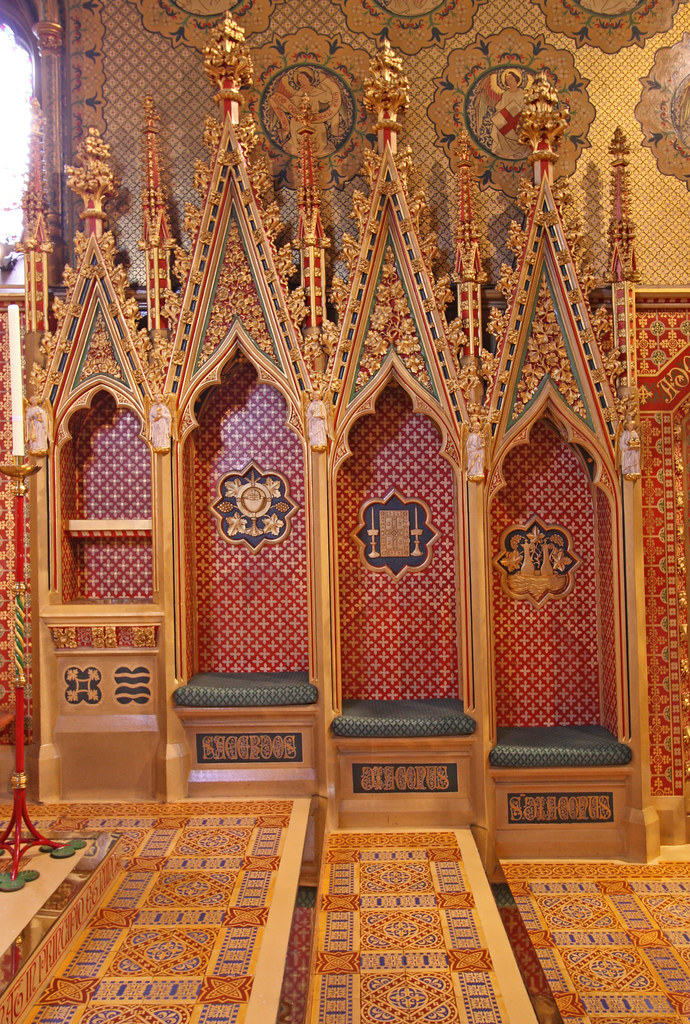

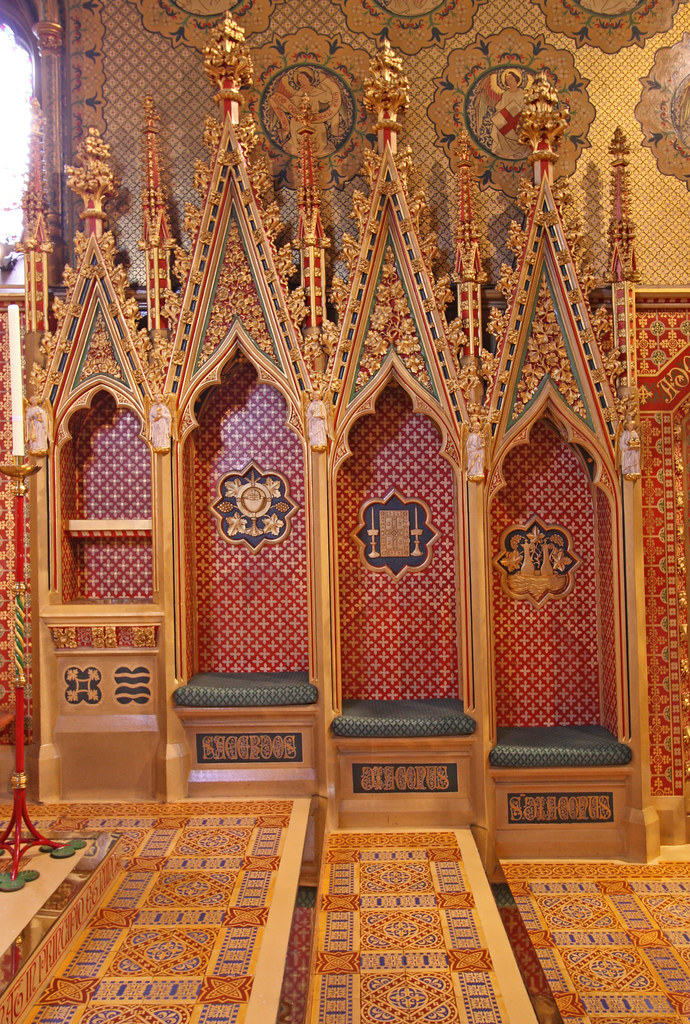

|

| The shelf and piscina are to the left of the priest's seat in this sedilia by Augustus Pugin at Saint Giles, Cheadle. |

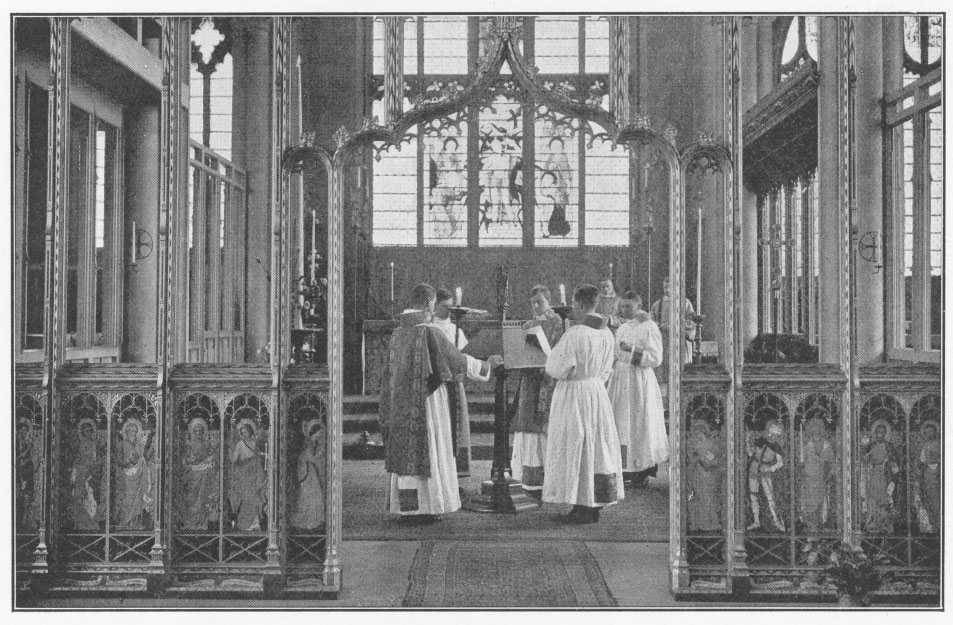

|

| This shows the mantled acolyte bringing the chalice in with a humeral veil, but the photo was intended to have this take place during the Offertory for the Prayer-book service, rather than during the Office/Kyrie as I described above. |

When the celebrant starts the Gloria, the rubrics say that he's given the tone for the first words, which varies by the occasion, from the precentor or a cantor. The modern practice is usually for the organist to play the starting pitches, but in the old, old days, the cantor would actually sing the words first, which the celebrant would then imitate. As mentioned in my article on low Mass, there are a handful of occasions where even the Gloria is modified with additional phrases for the Virgin Mary.

Collect, Epistle, Gradual, Alleluia/Tract, Sequence

While the celebrant is singing the Collect, which on certain days there might be three, five, or even seven (the rubrics stipulate the number of collects must always be odd, as God likes an odd number), the subdeacon prepares to chant the Epistle. On Sundays and feasts with rulers of the choir, the subdeacon chants from the pulpit or ambo. If there are two, as some medieval churches had, he stood at the one on the south or Epistle side. On all other days and on days of penitence, he would read it at the chancel step. Something I failed to mention in the low Mass article, by the way, is that there are no responses for the Epistle or Gospel in Sarum (Deo gratias or Laus tibi, Christe). They seem to have been of later invention.

|

| The subdeacon reading the Epistle from the chancel entrance. |

Once finished, he goes to the piscina where the cerofers assist him in washing his hands. The mantled acolyte then gives the subdeacon the cruets so that he can mix the water and wine in the chalice. He pours the wine first, but before applying water, he goes before the celebrant to have the water cruet blessed. I'm having trouble finding the Latin text of the blessing, but in English, the subdeacon says Benedicite/"Bid a blessing". The celebrant replies, "The Lord. By Him be it blessed from Whose side came forth blood and water. In the Name of the Father, etc."

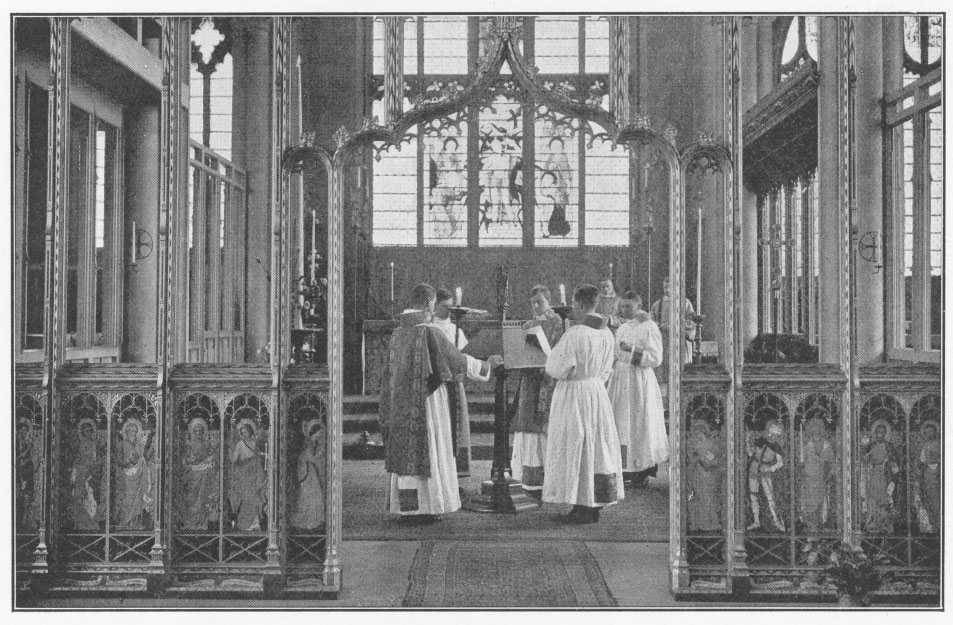

|

| The subdeacon prepares the chalice before a mantled acolyte. In this photo, they're standing before a side altar arranged for this purpose, rather than a credence. |

During this whole time the subdeacon has been preparing the chalice, the Gradual is sung. The Gradual got its name from this medieval practice still present in Sarum, which called for two boys in surplice to sing it from the step, or gradus, of the pulpit. It seems that when sung, they would repeat the first portion after finishing the verse except on doubles and days when there was a Tract. It's possible the choir joined in singing, and the boys only cantored the first words and the verse.

The Alleluia enjoyed a special solemnity which is gone in the Tridentine form. While the boys sing the Gradual, there are also two cantors, who are supposed to be canons in copes, who wait at a higher step in the pulpit. The Gradual finished, they sing the Alleluia. The rubrics have the choir and clergy all stand when the Alleluia begins. Only the celebrant and his two ministers may remain seated.

While Trent suppressed all the sequences save for the "five best" in the interest of shortening the liturgy, the Sarum Use had many more; somewhere in the range of 80 sequences, in fact. If there's a Sequence, the canons in copes begin it, and the choir join after. It's likely that the Sequence was sung in alternation. In the event of a sequence, the subdeacon waits until it begins to present the chalice to the celebrant.

If there's a Tract in place of the Alleluia, the Gradual is sung in the choir or at the chancel step. Then the Tract is sung by the rulers in the choir.

The Gospel, Creed, Homily

While the last chant is sung, the deacon goes to the piscina, where the cerofers assist him in washing his hands. Before he prepares the Gospel, he takes the thurible and incenses the altar: only the midst, for though there's no specific direction stating it, it seems the Gospel-book was placed at the north horn of the altar after the first incensing. Thus, by incensing only the middle of the altar, the deacon avoids incensing the Gospel-book before the proper time. (I wonder if this is also one of the reasons why the Missal rests on the south side of the altar up until this point: to allow the Gospel-book to rest on the opposite side.)

The deacon takes the Gospel-book and presents it to the celebrant for a blessing with the words Jube, domne, benedicere, just as in the Tridentine Missal. The procession goes out from the choir as such: thurifer, cerofers, (crucifer if on a double feast), subdeacon, deacon. If the Epistle has been read from the pulpit, the Gospel is read there too. The rubrics say that the deacon chants the Gospel facing north in the pulpit, while the subdeacon stands to his left holding the book in place on the lectern. The two cerofers are also there, standing on either side of the deacon and turned towards him. The crucifer also stands to the deacon's right. The problem is that in nearly every pulpit I've ever seen, it's impossible to fit so many people at once. Even having two would be a bit crowded for comfort. I suspect that in a modern celebration of Sarum, even if a parish had a pulpit, it would probably have to put the Gospel at the edge of the sanctuary (the normal Tridentine practice these days), or in the nave.

|

| The Gospel: one way to do it, at least. |

Now, something that took me a while to figure out was determining the proper place of the homily, or sermon. The standard practice today is to preach the sermon immediately after the Gospel. The Sarum rubrics say absolutely nothing about the sermon whatsoever; neither does Trent, for that matter. It simply followed the custom of Rome that placed the sermon after the Gospel. The problem I saw was that the Sarum rubrics instruct the deacon to carry the Gospel-book in procession back to the altar for the celebrant to kiss after he intoned the Credo. The sense of that rubric would be broken if it were interrupted by the sermon, but after some research, I discovered that the custom in medieval England and France in the Middle Ages was to have the sermon after the Creed, at the halfway point between the Mass of the Catechumens and the Mass of the Faithful! I also see now that, at least until recently, having the sermon and announcements after the Creed was part of the rubric of the Book of Common Prayer since its first edition. Furthermore, I've also read that the sermon takes place after the Creed in the traditional Dominican Rite, which shares many customs with Sarum. I've also seen a practice in the Anglican Use bridging the two practices by having the sermon after the Gospel, and announcements or notices after the Creed.

The reason for the discrepancy in practice may result from the fact that the Creed was introduced into the liturgy much later than the other portions here, but adopted in other parts of Europe long before it came into use in Rome itself (1014). Another complication is in the Tridentine pontifical Mass, which has the deacon chant the Confiteor and the bishop grant an indulgence before the Creed. This practice may also have varied in history. I'll have to look into it later.

The Bidding Prayers

The bidding prayers, if they were not prayed in the procession before Mass, were done "after the Gospel or Offertory". It's difficult to imagine them being made at any point in the Offertory without breaking its order, so I've decided to simply describe them here. They were read either from the pulpit (a 1928 Book of Common Prayer mentions bidding prayers made with the announcements, notices, and/or banns of marriage before the sermon, though that would place them after the Creed, in the place where the Intercessions of the Faithful are now found in the Novus Ordo Mass) or at the chancel step.

What made these bidding prayers peculiar in Sarum was that they were directed to be prayed in the vernacular, or "mother tongue". They vary a bit depending on which manuscript you find them. Here's one version:

Let us make our prayers to God, our Lord Jesus Christ, to our Lady S. Mary, and all the Company of Heaven, beseeching His Mercy for all Holy Church, that God keep it in good estate, especially the Church of England, our Mother Church, this Church, and all others in Christendom.

For our Lord the Pope, for the Patriarch of Jerusalem, for the Cardinals.

For the Archbishops and Bishops, and especially for our Bishop N., that God keep him in his holy service. For the Dean/Rector, or all other ministers, that serve this Church. (One variation of this: "For your ghostly father, and for Priests and Clerks that herein serve or have served, for all men and women of religion, for all other men of Holy Church.")

For the Holy Land and the Holy Cross, that God deliver it out of the hand of the heathen.

For the Peace of the Church and of the earth.

For our Sovereign Lord the King, and the Queen, and all their children.

For Dukes, Earls, and Barons, and for all that have the peace of this land to keep, all that have this land to govern.

For the welfare of N. and N., and all this Church's friends.

For all that live in deadly sin.

For our brethren and sisters, and all our Parishioners, and all that do any good to this Church or foundation. For yourselves, that God for His mercy grant you grace so to live as your soul to save, and for all true Christian people.

The priest then turns to the altar and the choir begins Psalm 66 (Deus misereatur) "without note". After the doxology, the choir continues:

Lord, have mercy.

(Priest) V. Christ, have mercy.

R. Lord, have mercy.

V. Our Father, etc... And lead us not into temptation.

R. But deliver us from evil.

V. O Lord, shew thy mercy upon us.

R. And grant us Thy salvation.

V. Let Thy priests be clothed with righteousness.

R. And let Thy Saints rejoice.

V. O Lord, save the King.

R. And hear us in the day we call upon Thee.

V. Give Salvation unto Thy people.

R. Govern them, and lift them up for ever.

V. Let there be peace in Thy strength, O Lord.

R. And plenteousness in Thy towers.

V. O Lord, hear my prayer.

R. And let my crying come unto Thee.

V. The Lord be with you.

R. And with thy spirit.

Let us pray.

God, Who with the Grace of Thy Holy Spirit dost pour the Gifts of Charity into the hearts of Thy faithful people, grant to Thy Servants and handmaidens, for whom we beseech Thy clemency, health both of mind and body, that they may love Thee with their whole strength, and with entire affection may perform those things which are pleasing unto Thee, and grant us Thy peace in our time, through Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Then, turning to the people, the priest says:

Let us pray. (kneeling)

For the souls of N. And N., Archbishops, Bishops, Clergy, Benefactors, etc., who have served this Church, or done any good thereto, or to this foundation, and for all souls whose bones rest in this Church and Churchyard, and all those who have given to this Church or foundation, rents, vestments, or other goods, whereby God is better worshipped in this Church, and the minister thereof better sustained; for all our Fathers' and Mothers' souls, our Godfathers' and Godmothers' souls, Brethren and Sisters' souls, all our Parishioners' souls, and for all the souls that have done any good to this Church, and for all Christian souls.

The priest turns again to the altar and the choir begins Psalm 129 (De Profundis) without note. After the doxology and Our Father, etc.:

V. Grant them eternal rest, O Lord.

R. And may perpetual light shine upon them.

V. From the gate of Hell.

R. Deliver their souls, O Lord.

V. I believe to see the good things of the Lord.

R. In the land of the living.

Absolve, we beseech Thee, O Lord, the souls of Thy servants and handmaidens, our relations, our neighbours, our friends, our benefactors, as well as the souls of all the faithful departed, from all the chains of their sins, that in the glory of the Resurrection they may be raised up to life, and breathe again among Thy Saints and Elect: Through, etc. May they rest in peace.

Amen.

The series continues with the

Sarum High Mass: Mass of the Faithful.