My girlfriend has been struggling for some time with the Catholic Church's current situation as a haven for banal liturgy, pedophilic clergy, and effeminacy (or so it would seem when one is frustrated). It's hard to blame her, as I sometimes feel embarrassed to be associated with the Roman church myself. The easy solution, you may think, is to recommend her to the local Latin Mass community, but her "brand" of medievalism shares Orthodoxy's consternation against the angel-on-a-pinhead-counting type of rationalization and legalism that has pervaded the Catholic world's intellectual circles since the age of scholasticism. True that these words don't mean anything to your average Catholic in the pew, but Latin Mass communities are practically built by eggheads whose idea of a good time is reading a commentary on Aquinas. Being an egghead herself, she does what most disaffected, liturgy-loving Catholics in her situation do: turn to the East.

This past Sunday morning, we visited a Russian Orthodox church in the outskirts of the city. "Tiny" would be an understatement, as it was established in a converted house well within a residential neighborhood. I don't think the congregation numbered above 20. And why the Russian church, as opposed to a larger Greek church in the city? Lauren is a bit of a Russophile and has some Russian ancestry. We both spent the summer reading Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov too, a tome chock-full of Russian Orthodox themes. I also knew that the celebrating priest was an expert on the Sarum Use of the Roman Rite (which I've blogged about extensively last year) with many articles about it on the web, so I wanted to see him in person.

Modern Medievalism and Orthodoxy

First, what does this have to do with the theme of "modern medievalism"? The answer is simple: as much as the Roman church embodies the word "medieval" as we think of it today, the Orthodox do a much better job of bringing medievalism to the modern world than we westerners do. Every Latin Mass is "compromised", if you will, by the newfangled Gregorian calendar and its artificial Easter dating. Most are celebrated in the trappings of Rococo barbarism branded as traditional because, in the literal sense, they were still fashionable in the 1950's. Baroque music is at least as likely to be heard as plainchant. If the Roman liturgy is truly older than that of Saint John Chrysostom, as certain apologists claim, it's only by accident on the part of westerners. The Orthodox, on the contrary, seem hellbent on giving their believers the impression that they've stepped into a time warp peering back to the apex of Byzantium's hold on the Christian world.

Now that I've set the story, I'll narrate to you my thoughts as I entered the church and pondered what made our eastern brethren different from us.

Attending Divine Liturgy, step by step

We were ten minutes late, but the Divine Liturgy being as long as it is, they were just getting started. A lot of regulars showed up much later than we did. I'm told that the Orthodox are not given to punctuality, and many come in and out of the church throughout the Liturgy without batting an eye; already one point in their favor, in my book. Ten minutes in, and the congregation was only a little more than half what it would become later in the day. Also of note: when we entered, I observed that women and men had segregated themselves into opposing sides of the church. I split off from Lauren after that, but when some families came in, they stayed together on what I understood to be the "men's side", so perhaps I made up that rule in my head entirely based off of a coincidence. Moving on....

Aside from what I perceived to be sex segregation, the first thing that struck me when I walked in was that the entire nave and sanctuary of the church, all in what was perhaps some guy's living room once upon a time, still looked "churchier" than most Catholic churches I've been to. Icons decked out all sides, and the sanctuary was sectioned off by an impressive iconostasis (considering the surroundings). These were definitely not a people who were concerned about offending their Protestant neighbors' sensibilities. They would probably not think whitewashing their walls or getting rid of their fine vestments would make them any more humble than they already are. (After all, they were worshipping in a house like the early Christians, or like underground Catholics in China. I doubt they need any more reminders about their position in society.)

After what felt like something six times longer than our fore-Mass (here I mean the preparatory prayers, Kyrie, Gloria), a lector in cassock stepped from the choir in the back to the center of the nave to chant the Epistle in English. Another gentleman stood beside him, following the English version immediately with a re-chanting in Russian. The church didn't have a deacon, so the priest chanted the Gospel. This was the first time I got a good look at him. He was a hieromonk (the word easterners use to describe a monastic priest), and appeared in the flesh as I imagined all priests should: clad in the finest vestments a church can afford, with a great beard and unclipped hair, just as virtually all our depictions of Christ have it. I've never bought the idea that a western priest should shave just because that was the fashion during the late Roman Empire. Do we want a priest to be an alter Christus, or a mock Roman senator? Another argument I've heard is that a priest with long hair and a big beard would scandalize people. (Who, your grandmother?) But then, why wear a cassock outside of the church? Indeed, why bother with the Roman collar at all? In the first world of the 21st century, a Roman collar is going to scandalize a lot more people than a beard if for no other reason than because the collar has become the universal sign of the pedophile.

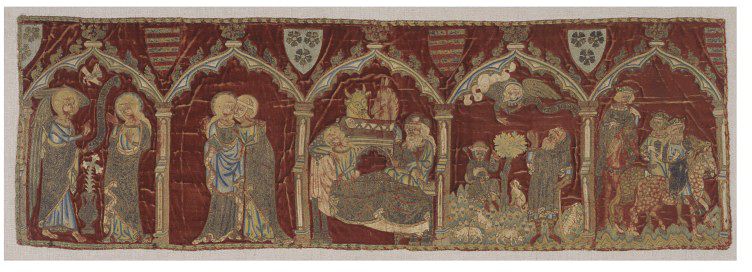

|

| Bishop Nikon |

After the gospel, the priest gave his sermon. A kind middle-aged guy who knew I was visiting and helped me follow along in a service book invited me to sit on a bench resting against the wall. As there were no pews and only a couple other benches beside the one I was sitting on, everyone else sat on the floor, Woodstock-style while the priest spoke. He wanted to expound upon a sermon of Bishop Nikon (Rklitsky's) on the Transfiguration and passed out printouts of that sermon to everyone (the following day was to be the feast of the Transfiguration in the old Julian calendar, which this church observes). The priest was very engaging and personable without having to resort to lame jokes, as one Latin Mass priest I know does. For a moment, I imagined I was really there with Peter, James, and John as Jesus revealed His divine nature to them. Most of the time, I can't wait for a sermon to be over, but I was sad when this priest ran out of things to say.

Following the sermon, the priest began the "Litany of Fervent Supplication", which corresponds to the prayers of the faithful in the Novus Ordo Mass. Latin Mass purists may get irritated when I say that I believe restoring the prayers of the faithful was one of the (very few) legitimate improvements of the Novus Ordo. I use the word "improvement" loosely because intercessions used to exist in the Roman liturgy (and continue to exist in the famous intercessions of Good Friday), but I can't go so far as to say "restoration" because I don't think the early medieval West had middle-aged women in pantsuits rasp the prayers out from the lectern. A handful of western churches, such as my Anglican Use parish, pray them in a sensible manner with a deacon, but it's a needle-in-haystack situation. (For further reference, I posted an example of the intercessions, or "bidding prayers", that existed in pre-Reformation England near the end of this article.)

Anyway, I smirked when the litany used charmingly old-fashioned phrases like "again we pray for our great lord and father, His Holiness Patriarch Kirill" and for "pious kings and right-believing queens" as though any still existed. After that, the priest said "as many as are catechumens, depart". The Eucharistic portion of the liturgy hadn't even started yet, but if I had gone to a Roman Mass, it would already be well into coffee hour by now. I had gotten a little tired of standing and contemplated taking the liturgy's cue to leave, but I then resolved to restrain by pathetically short westerner's attention span and see it through to the end. I also concluded that as a validly baptized Christian, I wasn't really a catechumen by Orthodox reckoning, just a schismatic. And so I stuck around.

A word on the music: one of Lauren's beefs with the western church, which I heartily agree with, is what some call the "low Mass mentality". Don't get me wrong, I like low Mass... in its proper context. But when it was developed in the later Middle Ages, it was supposed to allow a monastic priest to celebrate an additional Mass for his own and other intentions, beside the conventual solemn Mass that he and his brothers all attended. Later on, during the Church's great missionary age, the low Mass was very useful for priests stuck by themselves in strange lands without the resources to recreate Notre-Dame in the middle of Indian territory, or say in Ireland when priests were on the lam during the penal days. And even today, low Mass is great for weekdays when the pious faithful want to get in and get out for a boost of holiness before the start of the work day. I get it, truly. But at no point was the low Mass ever supposed to replace the solemn Sunday liturgy. Every Sunday is a feast, and a feast implies singing. Somewhere down the line, we in the west have supplanted "festivity" with "obligation", so it's no wonder we want to punch our timecards at church as quickly as possible and get back to football season.

So I was struck that at this tiny Divine Liturgy I was observing, attended more sparsely than even some weekday low Masses, everything was still sung from beginning to end. I'll hasten to add that the Divine Liturgy would probably take a long time even if it ever occurred to a priest to just recite the entire thing in the spoken tone. The choir was a mix of men and women singing the responses and other liturgical texts in harmony, but by no means dragging them out. They went through the Nicene Creed much faster than it would take us westerners to chant Credo I or III. I don't know if the Divine Liturgy has anything analogous to our long, melismatic Proper chants like the Gradual, but I didn't hear anything like that here. In truth, I was disappointed that I didn't hear anything like the deep all-male Russian chants you might find on YouTube with the droning, but I'm told those sorts of choirs are rare outside of Russia itself. Or perhaps it's just beyond this tiny parish's resources. Either way, the choir here seemed to exist just to lead the congregational singing. In America, though the schola I belong to actively tries to foster as much congregational singing as possible, sung Latin Masses tend to be showpieces for the choir as the congregation listens in admiration. (I've actually heard the line, "if you were at a symphony, you wouldn't climb into the orchestra pit to perform with the musicians, would you?")

| An iconostasis |

The priest withdrew behind the iconostasis for the anaphora/Eucharistic prayer, and for at least part of it, he closed an additional screen so that you couldn't see even the top of his head. My mind wandered for a while so I don't recall all the details, but I think the entire anaphora was sung aloud. There was no silent Canon as we have in the old Mass. Later, Lauren remarked to me that in the west, after the Counter-Reformation, we seem to have discarded visual veiling in favor of verbal veiling. We got rid of the rood screens to appease Protestant objections, but retained the silence, and the Latin language, to preserve a sense of mystery. The east, I would venture to guess, didn't see the need for a silent Canon or any problem with the common tongue because they already had the iconostasis. In my opinion, it'd be great for the Mass to make use of all of the above, but according to Cardinal Newman, you might as well celebrate Mass in the sacristy if no one can see the action. Apparently, most traditional Catholics agree with the sentiment, so rood screens won't make a comeback anytime soon.

|

| Communion eastern-style |

Naturally, just being a visitor, I refrained from Communion. Many people in attendance, who I assume are regulars, also refrained from receiving. I'm not sure if it's because this is normal for Orthodox churches the world over, or because the congregation is made up of "trads". (Nearly all the women also wore headcoverings like in trad Catholic churches, but not a mantilla in sight.) Again to the consternation of my friends who are 1962 purists, I admired the Divine Liturgy's use of both species and wished I could receive both in the context of the old Mass. The priest addressed the communicants by name, saying "the servant/handmaid of God, N., partaketh of the precious and holy Body and Blood of Our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ, for remission of sins and for life everlasting."

An aeon later, after the dismissal, the priest informally spoke to the congregation about things like Russian traditions regarding Communion, the vigil for the Transfiguration to be held that evening, and about the current attacks on Christian churches in the Middle East. Finally, he asked if anyone had any birthdays or name days coming up. One guy did, so the whole church sang "God Grant You Many Years" or something similar. When that was done, everyone dispersed to either the "parish hall" (another room in the house) or to receive a blessing from the priest. The guy who helped me follow along in the service book invited me to receive a blessing from the priest along with everyone else, but for the same reason I decided not to make signs of the cross Eastern-style, I decided not to go up for fear of mucking things up.

The fellow who had a birthday was, I think, also the choir director. He warmly welcomed me to the church and asked if I was a musician. I don't know what prompted him to ask since I didn't even sing the congregational parts, but I said I was, and he responded along the lines of, "if I had known, I would've invited you to join us in sightreading some of the parts." To which I replied, "thanks, but I'm not Orthodox." He continued, saying, "that's okay, I wasn't Orthodox when I began singing here, either." He then invited me to stay and eat lunch with the other parishioners. I would've taken him up on it if I didn't feel so awkward, but instead, Lauren and I left.

The ride home

Lauren enjoyed the Liturgy quite a bit, and I had a very positive experience about it and the community myself. In fact, if you've read up to this point, you might be wondering if I've thought of "going Dox" by the end of it all. In a word, no. And although I mused that I unwittingly tossed Lauren headfirst into Patriarch Kirill's clutches by indulging her with this visit, she actually came through it more comfortable with her Catholic identity. Although our proverbial pilgrimage to Moscow affirmed in both us everything we disliked about western spirituality, there was still something missing. Lauren iterated the four marks of the Church (one, holy, catholic, and apostolic) and said she believed the Orthodox came up short on the "catholic" part. After all, we visited a Russian Orthodox church, as distinct from a Greek or Serbian one. While it's true that the Roman Church also has eastern rites, and in the not-too-distant past also had ethnic Irish, Italian, Polish, and Korean parishes in America, these are all window dressing by comparison to the distinct ethnic character of the various Orthodox churches out there.

An Orthodox reading this will quickly object by saying that there's no ethnic requirement to joining the church. Indeed, I believe the priest at the church I visited was of Irish descent (just based on name and appearance; I didn't talk to him), and I'm led to believe that it's quite normal for Orthodox clergy in America to be of Anglo, Irish, German, or otherwise non-Eastern European origin. But still, just speaking personally as a non-Slav, I feel like even if I did have the urge to convert to Orthodoxy, I wouldn't feel completely integrated into the Orthodox world unless I went above and beyond, and became a cleric in the faith. Otherwise, I'd perpetually be a hanger-on, a token half-Anglo, half-Indonesian guy (if not the only half-Anglo, half-Indonesian guy in all of Orthodoxy). As a convert to the Roman church, while I do still feel like a bit of an outsider, this is more because I'm just a single person going to church without any family ties or little ones trailing behind me, rather than because of ethnicity.

In spite of all the eye-rolling induced whenever I read about the latest media stunt or soundbite surrounding Pope Francis, or my general cynicism about anything related to Vatican politics, I have to admit that the bishop of Rome somehow still supports a unity and catholicity you just can't find anywhere else in Christianity. I can look at photos of Japanese people attending Mass in Nagasaki after the bombs fell and think it makes sense, but think it would be bizarre if it were a Divine Liturgy instead. I can be irritated as hell looking over photos of the Eucharist being tossed like candy at World Youth Day in Brazil, but still feel the event is somehow relevant to me because I'm Catholic. I can have absolutely nothing in common with the average pew-warmer at the Catholic parish down the street, but what happens at his Novus Ordo Mass still matters to me more than what happens at an aesthetically perfect solemn Mass at Saint Clement's Episcopal in downtown Philly (though they are more Tridentine than Puginesque, but I digress). Much as I'd like to ignore the daily doings of Francis, his office somehow ties the ordinary Joe Catholic pew-warmer's fate to mine more than that of the most zealous Anglo-Catholic medievalist.

A Western Orthodox world

If I could build my own church, it would look like the Sainte-Chapelle and have daily solemn Mass and Office in the Sarum Use with a rood screen, choir stalls in the sanctuary, Communion under both species, less scholasticism and legalism, and some odd combination of both married secular clergy and celibate canons; and somehow still have a very active role in social justice and ministering to the poor of the area. As a young male convert to Catholicism with just enough education to enjoy armchair pontificating and not enough to be wise and content with what I have, I have the bizarre daily temptation to re-imagine the Church as I want it to be. Lauren, being a more masculine thinker than most women (don't tell her I said that, but honestly, when was the last time you heard of a single young female who thought of converting to Orthodoxy because Catholicism is too effeminate?), sought solace in the East but came through with a reassurance of Catholicism's catholicity, despite itself.

My imaginary church will never exist under the auspices of Pope Francis or (probably) any of his successors in my lifetime. The closest it's ever come would be under the extremely niche communities of Anglo-Catholics (such as Saint Clement's, as I mentioned above) or in so-called Western Orthodox communities. The priest of the Russian Orthodox parish I visited is an expert on the Sarum Use and, I imagine, has celebrated it many times before if he doesn't now. These communities are havens for thinkers such as Lauren and myself, and I'm sure some of them even read my blog.

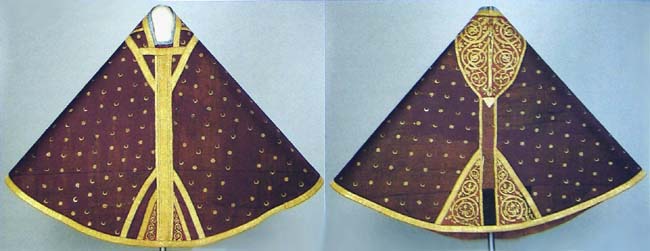

|

| This Western Orthodox bishop (?) is precisely what I imagine all western churchmen ought to look like |

My last thought for this entry: if reincarnation were true, I'm pretty certain I would have been Henry VIII in a past life. No other historical figure so embodies the "if I could build my own church" sentence I wrote better than he. Contrary to popular belief, Henry didn't create the Church of England just because he was randy. Any other king in his position would have just taken Anne Boleyn as a mistress and carried on with life. But before Henry became king, he was a young man groomed for a career in the clergy while his older brother, Prince Arthur, was set to be king. Indeed, his father named his firstborn "Arthur" out of a belief that he, the first of a union between the feuding houses of York and Lancaster, would lead England to a new golden age just like the king of myth. Young Henry, some said, would serve the realm as Archbishop of Canterbury beside his elder brother.

|

| Henry VIII before he was fat |

So when Arthur died and Henry became heir, it's no surprise that his background as a potential churchman shaped his approach to the kingship. Henry's piety led him to come to the Papal States' defense during the Italian Wars. With the aid of Saint Thomas More, he published the Defense of the Seven Sacraments against Luther and was named by the Pope a "defender of the faith". When the continuation of the Tudor line came into question, it wasn't enough for Henry to just take a mistress as any other king would have done. He had to have his union validated by the Church, and if the Church wouldn't acquiesce (and honestly, if Katherine weren't the Holy Roman Emperor's aunt, the annulment probably would have gone through), he would have to take matters into his own hands.

Still, for the average Englishman, nothing changed under Henry's Church of England at all. At most, he introduced the "for thine is the kingdom" doxology to the Lord's Prayer, but that was already in Eastern usage, not a Protestant innovation. Lutheranism was still condemned in Henry's church. So ironically, I don't see Henry VIII as a Protestant at all. He was instead, perhaps, the first Western Orthodox; for if every king had followed his example, the West would have broken into national churches while otherwise remaining completely apostolic. The Pope would have remained "patriarch of the west" but with no real power outside the see of Rome.

And therefore, every day in between brushing my teeth and flossing, I look into the mirror and ask myself, "have I become Henry VIII?" The answer remains no, and it's not just because I decided to lay off the enchiladas. No, friends. Lauren and I will remain where we are, loving the Roman church despite Her best efforts to eject medievalists to the dustbin of history. Apologies if I offended anyone in the process.