As some of you may know, I didn't get accepted to graduate school, so I'm contemplating a change of career. But in all the confusion, I forgot to share with you one of my writing samples, an essay on the history of the Dominican Order. It was one of several topics I had to choose from for a midterm paper for a particular class, and I could only cite from a preset list of sources. So if that's why I neglected to cite from your favorite seminal work on the Order, now you know. Enjoy!

Update: a few minutes after I posted this, a friend of mine remarked, "just in time for the feast of St. Dominic". Lo and behold, I check and find out out that today, in the pre-Vatican II calendar, is indeed the feast day of Saint Dominic. I have to confess that apart from my chosen patrons, I don't really keep on top of saints' days so there is no way I posted this essay on purpose, even subconsciously. Truly, I just couldn't think of anything better to post today. This is either providential or extremely coincidental.

Update: a few minutes after I posted this, a friend of mine remarked, "just in time for the feast of St. Dominic". Lo and behold, I check and find out out that today, in the pre-Vatican II calendar, is indeed the feast day of Saint Dominic. I have to confess that apart from my chosen patrons, I don't really keep on top of saints' days so there is no way I posted this essay on purpose, even subconsciously. Truly, I just couldn't think of anything better to post today. This is either providential or extremely coincidental.

God’s Advocates: The Ascent of the Dominican Order

On the eve of the 13th century, it seemed that

Christendom was a house divided against itself.

The eastern churches had already long since severed communion with

Rome. Meanwhile, the flames of Cathar heresy

were spreading across southern France, the so-called eldest daughter of the

Church, with alarming speed. The classic

monastic orders were accused of standing idly in solitude as their communities

were falling into the hands of heretics, living in violation of their vows of

poverty and chastity, or both. Who, in

those turbulent times, would stand in defense of the Catholic Church against

the teachings of the Cathars and those others who accused the Church of

straying from the gospel’s narrow path?

Among these few, Dominic of Osma and his Order of Preachers arose to

take up the cause of orthodoxy. The

Dominican friars would go on to enjoy great prestige in the urban and

intellectual life of Europe for the rest of the medieval era. This essay will examine the personal

experiences of the Order’s founder, a treatise by a Dominican Master on the

formation of Preachers, and other accounts of the Order’s activities to

demonstrate why the Dominicans were one of the most popular and successful

orders of the age: because they were the most adept of all the religious orders

at fulfilling the Church’s need for educated, articulate defenders. Unlike the cloistered monks, the Dominicans

actively engaged the laypeople of the cities throughout western Europe,

bringing the message of the established Church to them in a way they could

understand.

|

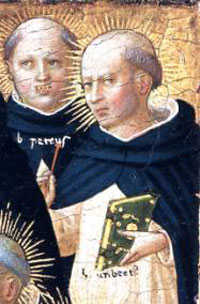

| Saint Dominic as painted by Fra Angelico, also a Dominican |

The Order’s roots begin with its namesake, Dominic of

Osma, then a humble religious priest. In

1205, he accompanied the bishop of Osma to visit Pope Innocent III in

Rome. Along the way, the two journeyed

through southern France, the stronghold of the Cathar sect. There, they met the Cistercian legates sent

by the Pope to dispel the heresy and diagnosed just why the Cathars were so

successful in leading the people of the region astray: “its clergy had grown

amoral and overrich. And they told the

pope that ‘in order to shut the mouths of the wicked, the clergy must follow

the Divine Master’s example in the way they acted and the way they taught,

stand humbly in the sight of God, go on foot, spurn gold and silver; in short,

they must imitate the Apostles’ way of life in everything they did.’”[1]

The clergy, in short, had grown lax with centuries of

privilege and patronage. Their demands

for alms and obedience fell on deaf ears when they were put in competition with

the “perfect” of the Cathars: the purest of the sect’s ranks, who refused money

and possessions, abstained completely from sex, and subsisted on a very strict

diet. While those rules may not seem

different from the vows which professed monks must observe, the Cathars taught

a radically different doctrine. Like the

Manicheans a millennium before, the Cathars preached a dualistic reality where

a God of light and a God of darkness were equally matched in a great battle for

the fate of the world. Where the

Catholic God was the creator of all material things, the Cathar was expected to

shun them because they were a product of the evil deity. The inherent evil of possessions gave the

Cathar “perfect” a special incentive to live out the ascetic ideal; in doing

so, their example put the Catholic clergy, even the most strictly observant

religious of their time, to shame. The

“perfect”, furthermore, gave their weaker brethren only one condition for

achieving salvation: “all they needed to do, in order to impregnate them with

the coveted Spirit, was to stretch out their hands over them before they died.”[2] It was a lot less to ask for than the

Catholic clergy, who expected alms, penances, pilgrimages, and confession to

men far less impressive than the Cathar leaders.

|

| Left: Pope Innocent III excommunicating the Cathars (also called Albigensians). Right: The Albigensian Crusade. |

A call to the true spirit of poverty, then, was the

prescription which Dominic brought to his pontiff in Rome. Innocent gave Dominic his blessing and sent

him back to the Cathar lands. The people

of Languedoc saw Dominic and his bishop return on foot, clad in simple garb, as

poor as their opposition. The two sides

engaged in one dispute after another, but victory for the Cathars would not

come so easily this time, for Dominic was a man of letters. He knew Occitan, the language of the

region. He carefully prepared his

arguments ahead of time, in writing. In

the “tournaments” arranged by the nobles and townsmen, he matched the Cathars’

objections point by point, and in the eyes of his judges, stood

victorious. This initial victory, won

through the double-edged sword of poverty and reason, would shape the methods

of Dominic’s followers for centuries to come.[3]

Dominic cemented his work in Languedoc by founding a

convent adhering to the strict rule of St. Augustine, competing directly with the

Cathar houses for women. From there, he

attended the Fourth Lateran Council which, despite its attempts to reign in the

creation of new religious orders, authorized him to form the Order of Preachers. The Dominican friars were a new force to be

reckoned with: they did not seclude themselves behind walls, but worked in the

towns and freely mingled with the laity.

Their rule, based on that of Augustine, stipulated, “We shall receive no

property nor income of any kind.”[4] It was a stark departure from the way

monasteries supported themselves, which typically involved the collecting of

tithes from tenants on their lands, just as feudal lords did. The Dominicans’ rule even dispensed them from

praying the hours of the Divine Office, which all other religious were obliged

to observe, when they had a mission to perform among the people.

The

very name of the Order says much about their cause: to win the hearts and minds

of the laity through the use of argument.

Humbert of Romans, fifth Master of the Order, penned a manual “On the

Formation of Preachers” which illustrates how a friar would translate his

method of argumentation from the university lecture hall to the pulpit.

Now

there are some preachers whose preparatory study is either all devoted to

subtleties... or, at other times, it is exclusively devoted to looking for

novelties, their intention, like that of the Athenians, being always to find

something new to say... But a good preacher's concern is rather to study what

is useful.[5]

|

| Humbert of Romans, fifth Master of the Order |

All the Order’s talent still would not have assured their

preeminence in the life of Christendom if it were not for the support they

enjoyed from Rome. Pope Innocent’s

entire legacy was based on the assertion of papal primacy.[7] To assert his influence over the kings of

Europe, he first had to establish firm control over the bishops. Powerful though the papacy was, it was still

a tall order in a world of decentralized authority, where bishops reigned

supreme within their dioceses. The

Lateran Council charged bishops with the duty of stamping out heresy by any

means necessary, and threatened those who failed to contain the threat with

deposition.[8]

However,

a more reliable solution for the Pope was to sidestep the bishops

entirely. The Dominicans, among other

mendicant orders, were exempt from the local bishop’s authority in a number of

ways. The Council, for instance, forbade

anyone “without the authority of the Apostolic See or of the Catholic bishop of

the locality” from preaching, whether publicly or privately, under pain of

excommunication.[9] Even a priest in good standing could not

simply go to the next town and preach without that bishop’s permission. The Dominicans, to the contrary, held Rome’s

trust and were authorized to go preach wherever they desired. With no restrictions on where they could work

or build monasteries, the Dominicans established themselves all over Europe,

especially at intellectual centers from Bologna, to Montpellier (in the heart

of the formerly Cathar stronghold in Languedoc), to as far as Oxford, where

they were nicknamed the Blackfriars after their distinctive black cloaks.[10] The papacy, in turn, used its close

relationship with the Order to tighten its hold on the universities. With loyal Dominicans at the forefront of so

many schools, the papacy could ensure the dissemination of orthodox teaching

everywhere; under the Order’s auspices, Catharism was doomed to extinction.

|

| Santa Maria Novella, the chief Dominican church in Florence |

Dominicans

continued to play a large part in the history of the Church long after the

Cathars had been eradicated. If the

Renaissance first emerged from the city of Florence in the course of the 14th

century, the Blackfriars can proudly claim to have been among its

architects. Gene Brucker asserts that

the Dominicans were “the most active and distinguished” religious order of that

era.[11] Where other orders in the city, such as the

Camaldolese, suffered from poor education, family allegiances, and moral

laxity, the popes could rely on the Dominicans to produce capable

administrators and irreproachable spiritual leaders. From Florence alone, the Order could boast of

one canonized saint and three blesseds, including the renowned artist Fra

Angelico. Brucker adds, “A more

significant index of distinction is the number of Florentine Dominicans who

became bishops. Twelve held sees between

1360 and 1430, and another (Leonardo Dati) was elected general of the order.”[12] The most remarkable of these prelates was Fra

Antonino Pieruzzi, elevated to the Archbishop of Florence’s throne in

1446. A man of education and piety, he

demanded that the priests of his diocese actually carry out their spiritual

responsibilities. When words failed, he

had no qualms with imprisoning or even torturing priests who were lax in their

duties. At the same time, Antonino was

not unbending to the realities of his city: merchants were children of God just

as much as knights and peasants, and they could carry out their trade

honorably. “Just prices” were subject to

the unseen forces of the market.[13] He was later to be proclaimed a saint.

From

the Order’s humble origins under Dominic to the flowering of the Renaissance in

Italy, the Dominicans’ dual application of education and poverty gave them the

edge needed to win the respect of both the Church’s hierarchy and the faithful

at large. Like the Jesuits of the

Counter Reformation period, the Dominicans of the Middle Ages served as the

Pope’s own shock troops in a war against heresy. They produced a legion of saints and achieved

a foothold in institutions of higher learning across the Catholic world and

defined its mode of thought for centuries to come. Nowhere is their legacy more felt than in the

canonization of Thomas Aquinas and his Summa

Theologiae as the definitive treatise on Catholic theology. When the Council of Trent was finally

convened to answer the challenges of Protestantism, two books were laid upon

the altar: the Bible, and the Summa. Surely, no Dominican could ask for a greater

proof of his order’s contribution to the intellectual treasury of his church.

Works

Cited

Brucker, Gene A. Renaissance

Florence. New York: John Wiley &

Sons, 1969.

Duby, Georges. The Age

of the Cathedrals: Art and Society, 980-1420. Translated by Eleanor

Levieux

and Barbara Thompson. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1981.

Hollister, C. Warren,

Joe W. Leedom, Marc A. Meyer, and David S. Spear, ed. Medieval

Europe: A Short Sourcebook, Fourth

Edition. McGraw-Hill

Humanities: 2001.

[1] Georges Duby, The Age of the Cathedrals: Art and Society,

980-1420, trans. Eleanor Levieux and Barbara Thompson (Chicago, University

of Chicago Press, 1981), 139.

[2] Ibid., 133.

[3] Ibid., 139.

[4] Ibid., 140.

[5] Humbert of Romans, “On the

Formation of Preachers,” in Medieval

Europe: A Short Sourcebook, Fourth Edition, ed. C. Warren Hollister et al. (McGraw-Hill

Humanities, 2001), 247.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Duby, 137.

[8] “A Canon from the Fourth Lateran

Council”, in Medieval Europe: A Short

Sourcebook, 255.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Duby, 141.

[11] Gene A. Brucker, Renaissance Florence (New York: John

Wiley & Sons, 1969), 199.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 201.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete