|

| From a Sarum Missal |

[The liturgy of pre-Reformation England has been a subject of interest to me ever since I became Catholic in the first place. I'd go so far as to say that attending a high Mass according to the Use of Sarum is part of my "bucket list". I plan to write a series outlining the differences between the liturgies of Sarum and of 1962, but before I get to that, I ought to introduce this series with a history of the Sarum Use. None of this will be new to Sarum enthusiasts (all 6 of you out there in the entire world), but it'll be a good primer for the uninitiated.]

The traditionalist's bedtime storybook account of history might have us believe that the Roman Mass began when Christ in the upper room, adorned in fiddleback chasuble and an abundance of lace, uttered Te igitur, clementissime Pater in the Emperor's Latin. The Apostles then spread the "Mass of All Time" to the four corners of the earth, where it was transmitted faithfully without any addition or subtraction across the ages until 1965, when Bugnini and his cronies imposed vernacular worship, liturgical dance, polka Masses, and Masonic banality from on high. The late Archbishop deserves credit for somehow being able to radically reinvent the worship lives of a billion people by committee, but change itself has been a constant companion in the history of the liturgy.

In fact, in the early Middle Ages, worship was as feudalized as government. Just as every lord was virtually sovereign in his own territory, so too did every bishop govern how the liturgy was to be offered in his own diocese. This great variety of forms seemed like anarchy to Charlemagne, who ordered that the Roman Rite be adopted throughout all his realms for the sake of uniformity. (Ironically, the influence that Charlemagne wielded was so great that the liturgy of the Franks, in turn, changed the way the Mass was celebrated in Rome itself.) The battle for uniformity in worship played out differently in the other regions of Europe. It was never truly and completely won in England until Cranmer imposed his Prayer Book in 1549, but when discussing the liturgy of England prior to the Protestant Reformation, one form deserves examination above all the others: the liturgy of Sarum.

The Course of Sarum: From the Norman Conquest to Now

|

| Saint Osmund, second Bishop of Salisbury |

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, they brought French language, French literature, French law, and French liturgy. In an act of benevolent nepotism, William the Conqueror appointed his nephew, Saint Osmund, who had formerly served as Lord Chancellor for eight years, Bishop of Salisbury in 1078. There, in the settlement which was then also called by the Latin name of Sarisburium or Sarum for short, Osmund undertook the great task of revising and codifying the liturgy in his diocese into something which would satisfy Normans and Saxons alike. He did not invent; A.H. Pearson observes in his introduction to The Sarum Missal in English that the rites Osmund produced bear great similarity to those of the see of Rouen, which at that time was also the capital of the Duchy of Normandy. "The Epistles and Gospels, the custom of Rulers of the choir, the procession from the sacristy with the elements, and that of the Gospel, were the same as in the Sarum rite".

The Ordinal of Osmund naturally found favor with the new generation of Norman bishops. Within a century, the Use of Sarum became the predominant form of liturgy in England. While a number of other uses developed, such as those of York and Hereford, even those uses drew heavily from the Sarum books. Certainly, no other use in England could claim as much cultural impact; Sarum was adopted in Winchester Cathedral, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, London, all the chapels royal, and even Canterbury. Canon J. Robert Wright's essay on the Sarum Use notes that between the introduction of the printing press and the imposition of the Book of Common Prayer in 1549:

"As regards the Missal, there were 51 printings of the Sarum as compared with York 5; of the Sarum Breviary 42, the York Breviary 5; of the Sarum Manuale, 13 editions but of York 2; the Sarum Processional saw 11 printings and that of York 1; of the Ordinal 4 at Sarum and 1 at York; and of the Sarum Primer 184 (!!) compared with only 5 editions of the Primer from York. All told, more sources survive for the Use of Sarum than for all other medieval English rites put together."

King Henry VIII, after being declared Supreme Head of the Church in England, ordered the suppression of all other uses in favor of Sarum, though this decree was not to last long before his death and the arrival of the Prayer Book under the boy king. Queen Mary temporarily restored the Use of Sarum throughout the realm. She ordered a reprint of the Sarum books in 1555, and was wedded to Prince Philip in Winchester Cathedral according to the Sarum Manual. That was the last time the Sarum Use was to enjoy any official status in the English Church. The last reprint of any Sarum book was of the Manual in 1604, by exiled Jesuit priests of the English College at Douai, France. The English Jesuits, however, soon adopted the Roman books exclusively, and the Use of Sarum was forgotten for two centuries.

|

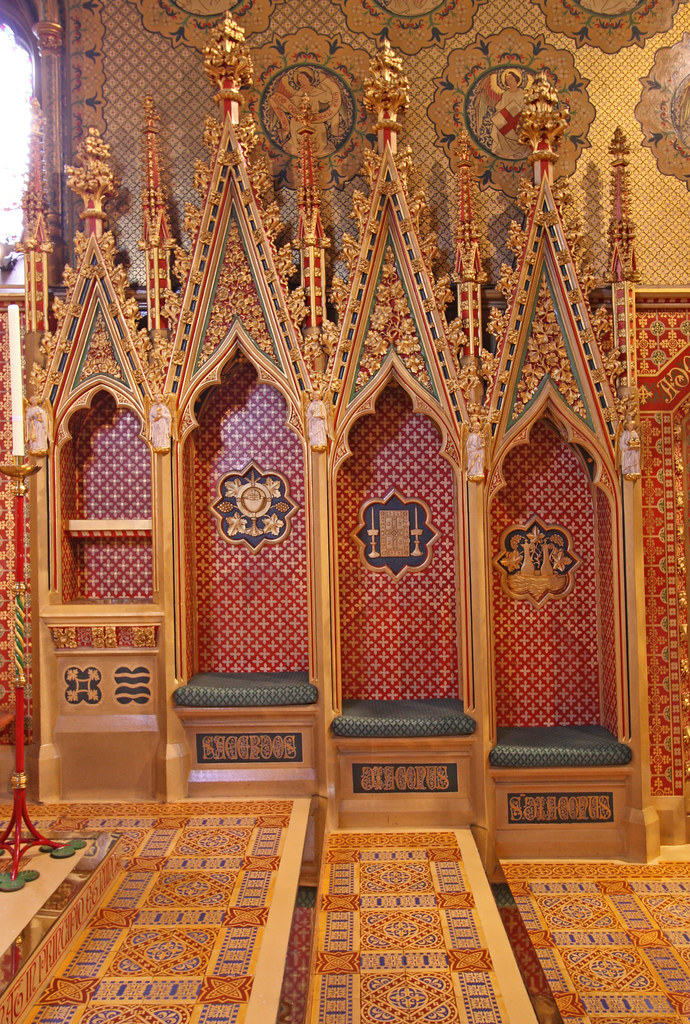

| Pugin's Sarum-style sedilia at Saint Giles, Cheadle |

The medieval revival in the Victorian age seemed to give the Use of Sarum a new lease on life, at least among academics and eccentrics. Augustus Welby Pugin naturally designed all of his churches in the expectation, however unreasonable, that they would house celebrations according to the Sarum books. (Most of his churches, for example, have seats for the clergy in which the priest sits higher and closer to the altar than the deacon, who in turn sits higher and closer than the subdeacon. The Roman practice has the clergy sit on a bench in equal height, with the priest in the middle.) With the restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850, Pope Pius IX supposedly gave the English bishops the option of restoring the Use of Sarum, but they chose to stick with the Roman books instead. The Anglicans of the Oxford Movement took far more interest in Sarum than the Catholics, but even they mostly limited it to a reference for which to dress up Prayer Book services in a more Catholic and ritualist appearance.

A few modern celebrations of the Sarum Mass, all under the auspices of the Roman Church, deserve mention. The Rev. Seán Finnegan gives an account of one from the '80s:

"The first I heard of was in Englefield Green, Surrey, where in the mid-1980s the inappropriately baroque Catholic parish church was the setting for a Mass as part of the celebrations commemorating Runnymede, the nearby setting for the signing of Magna Carta in 1215. Deacon and Subdeacon wore fancy baroque dalmatics stiff with gold braid, while the celebrant wore a 70s striped Slabbinck creation with a high collar and overlay stole. And yet it was still beautiful."

Another celebration took place at Merton College, Oxford in 1996 for the feast of the translation of Saint Frideswide. Merton College hosted another Sarum Mass the following year for Candlemas, for which there is a series of recordings on YouTube, the first of which I post below:

The most recent occurrence I know of was celebrated in 2000 by the Most Rev. Mario Conti, then Bishop of Aberdeen, at the King's College Chapel at the University of Aberdeen for the 500th anniversary of its founding.

Why Sarum Matters

Up to now, I admit I haven't demonstrated how the Sarum Use has any relevance whatsoever to the average Christian in the pew. The preceding examples of its revival were all organized either for the attendance of academics, or to mark historic events. That would seem to damn the Sarum Use to the anachronistic world of pipe-smoking, cape-wearing young fogeys in tweed jackets and bow ties. I can see it already: a discussion at the dinner table is centered around whether acolytes should wear tunicles, and every other sentence is punctuated by a Chesterton quote which isn't at all relevant to the topic but still accidentally makes the speaker sound like a genius. If these are the only people the Sarum liturgy can speak to, then it's dead on arrival.

The more important question is: how could the Sarum liturgy, which was used throughout England for 400 years, not have a lasting impression on the culture of the English and English-speakers around the world? I hope to uncover some of the Sarum Use's treasures in language and ceremonial in following posts. For now, it's worth observing that the most recent celebration of the Sarum Mass by Bishop Conti took place in Aberdeen in the northeastern region of Scotland, which actually had its own use. The Sarum Use was never celebrated there before. That a prince of the Church would celebrate the Sarum Use there demonstrates three things: first, that there should be no shame for any priests who wish to adopt the Sarum liturgy, at least for occasional use. Second, that celebration of the Sarum liturgy is by no means bound only to parts of the world where it had been celebrated locally. If it can be celebrated in northern Scotland, it can just as well be celebrated in the United States, Canada, or Australia. And finally, that the Sarum liturgy can be used apart from exercises in historical re-enactment.

I hadn't been completely convinced of this last point myself until I saw, a few days ago, an order for Compline from the Sarum Breviary in Indonesian! You can view it here if you don't believe me. Now, speaking as someone of half-Indonesian descent, I can tell you that the presence of Catholicism in that country, which is the most populous Muslim country in the world, is quite negligible. Nevertheless, if someone can appreciate the beauty of the Sarum liturgy enough to translate it into Indonesian and set it to square notation, there's absolutely no reason why those of us in the English-speaking world who are far more touched by the influence of Sarum can't investigate the treasures of pre-Reformation England as well.

The series continues with a comparison, step by step, of the Sarum and Tridentine low Mass.

The series continues with a comparison, step by step, of the Sarum and Tridentine low Mass.

|

| A Sarum processional chant |

Great info!

ReplyDeleteHave you by any chance listened to any of Michael Davies' talks on this subject on keepthefaith.org? I think the series of lectures was called "the evolution of the rites" or "history of the roman rite" or something. In one of them he talks about the Sarum liturgy in great length. He, being welsh, had a fascination with the Sarum.

Might be worth checking out. His talks on the liturgy are always fun to listen to.

If you can find a link, please post it so I can listen to it.

DeleteJames,

DeleteIf you go to this page (http://keepthefaith.org/searchResult_speakers.aspx?manufacturer=19) and click on page 2 you'll see half way down a series of six lectures called "Evolution of the Rites of the Mass". I can't remember is Sarum is dealt with in 4, 5, or 6 because its been a while. But I actually recommend listening to the whole series. In fact I recommend listening to each and every one of his talks on the liturgy. Amazing stuff.

I'm starting to think that chantry and gild masses should be revived, too. Both of which were a major component of pre-reformation English Catholicism.

ReplyDeleteMr. Griffin by chance have you read Stripping of the Altars?

And do you have any idea why the restored English hierarchy stayed Roman in their liturgical books? Familiarity? It is what the Pope uses and whatever he uses is automatically superior to all others type thinking? Perhaps, something else?

I've read large parts of it. I wish I had a copy on hand to refer back to at leisure.

Delete"And do you have any idea why the restored English hierarchy stayed Roman in their liturgical books? Familiarity? It is what the Pope uses and whatever he uses is automatically superior to all others type thinking? Perhaps, something else?"

It's most certainly the spirit of ultramontanism at work. The greater part of the English Catholic hierarchy wished to be completely Roman, adopting Roman books, Italianate architecture, and awful Italian music. Though there's no concrete proof for Pius IX allowing the wholesale restoration of Sarum, I wouldn't be surprised if it happened. Pius IX did certainly grant the clergy of England the privilege of wearing the simar: a black version of exactly the same type of house dress as his own. This explains why among traditionally-leaning English clergy, you might see them wearing a sort of cassock with double-sleeves and a shoulder cape.

As one of the other 6 Sarum enthusiasts--delightful! I look forward to more.

ReplyDeleteNot as learned on this rite, but have always enjoyed the different rites/usages, especially within the "Roman family". Will read it all, thank you and keep up the good work.

ReplyDeleteJoe

We frequently celebrate the Sarum Mass here at Prince of Peace Church in Vandalia IL USA, and have been using it since 1989. It inspires with its lofty and eloquent prayers that address God directly from the spirit of the celebrant.

ReplyDelete