(If you missed Part I, click here: The Revolution is Over.)

The Death and Return of King Arthur

Britain, once a powerhouse of the

Enlightenment (home of such thinkers as Sir Isaac Newton, the economist Adam

Smith, and the historian Edward Gibbon), acutely felt the excesses of the

French Revolution. As France burned, nobles and Catholic priests fled the country, seeking refuge in the borders of their former enemy across the Channel. The beheaded king’s brother, Louis Stanislas, Count of Provence, spent

several years living in exile in England. During these years, the Protestant English

developed a grudging respect for the French clergy in exile, and even

acknowledged the Roman Church’s proper place in France as a source of moral

authority. Meanwhile, they grew a deeper appreciation for their own monarchy as

a stabilizing force in the tumultuous world of politics. The time was ripe for

the English to look into their hearts, and their own heritage; not at the ruins

and verse of long-dead Greek civilizations, but in the works of their own medieval,

Christian ancestors.

Napoleon’s defeat ushered the return of

two kings, both issuing from Britain. The Count of Provence returned to France,

after an extended stay in England, as King Louis XVIII. But more remarkably for

us, in 1816 (a year after Waterloo), Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur was reprinted after having been out of publication

and forgotten for nearly 200 years. When

it first appeared in 1485, Le Morte

was an anthology, like a “greatest hits” of the tales of King Arthur; from the

founding of the Round Table, to Lancelot’s adultery with Guinevere, the tale of

Tristan and Isolde, the quest for the Grail, and as the title suggests, Arthur’s

death at the hand of his own son; all in one convenient package.

For us, Le Morte d’Arthur is the

foundation of classic fantasy fiction. But for a firebrand Protestant of the

Reformation, it was a pack of lies, superstition, and popery. Their descendants

in the Age of Reason were likely to see it as either quaint or absurd as a Monty Python skit; in both

cases, irrelevant to the pursuit of higher knowledge. Thus, it was consigned to

the dustbin of history for a couple of centuries.

|

| From Aubrey Beardsley's edition of Le Morte d'Arthur. Whoever said strange women laying in ponds, distributing swords is no basis for a system of government? |

But with the rejection of the Age of

Reason and neoclassicism, and the birth of a new Romantic movement, King Arthur

would come to symbolize a nobler, purer, simpler Britannia. It hearkened back

to an age when chivalry and courtly love were the order of the day, and the king

was a pious Christian who personally vanquished evil with lance in hand, rump

in the saddle. Of course, it was a bit awkward that the source material

contained as much sex and betrayal as an HBO series. Furthermore, the author

himself was a robber-knight, more at home in Game of Thrones than the Round Table. Malory wrote Le Morte from prison, where he was serving time for plundering abbeys and terrorizing monks

with a small army, attempting to murder the Duke of Buckingham, possibly two

counts of rape, and worst of all, fighting in the wrong side of the Wars of the

Roses.

Nevertheless, Le Morte was an invaluable window into Britain’s Arthurian

tradition, and the following years since its return saw authors adding,

embellishing, or retelling the tales of mythic and medieval Britain with ever

greater enthusiasm; the most famous being Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott in 1832 and Idylls of the King in 1859. The latter,

which sold 100,000 copies in its first week, reworked the Arthurian legends to

suit the mores and needs of Victorian society. For instance, whereas the Malory

version traced Arthur’s downfall to his son Mordred (born of an incestuous

union with his half-sister, Morgause), Tennyson reworked the destruction of the

Round Table to hinge largely on Guinevere’s adulterous affair with Lancelot. In

Tennyson’s worldview, the fate of the kingdom was closely tied to the personal

moral integrity of the queen. This is, of course, the ideal that Victorian

Britons grew to project onto Queen Victoria herself, whether she wanted it or

not.

|

| Prince John: from champion of church reform to Disney villain. |

Meanwhile, other authors such as Sir Walter Scott tried their hands at retelling, or perhaps reinventing, the

historical Middle Ages. The Age of Reason’s premier historian, Edward Gibbon, infamously

dismissed the entire medieval period as “the triumph of barbarism and religion”.

It was fashionable to cast the whole period as one dominated by Crusades,

Inquisitions, witch-hunts, superstitions, and remarkable lack of hygiene; in

short, a thousand-year nightmare in between the glories of the Roman Empire and

the present, “civilized” era. Walter Scott turned this picture on its head with

his novel Ivanhoe. Published in 1820,

it tells of a knight in 12th-century England in the service of King

Richard the Lionheart. There’s a crusade, a tournament, romance, Robin Hood,

and evil Prince John mucking things up while Richard is away at war: all the

ingredients to tell a good medieval adventure tale. John Cardinal Newman said

that Scott, through Ivanhoe, “had

first turned men's minds in the direction of the middle ages”. So profound was

its influence that it’s hard to believe that before Ivanhoe made its way to bookshelves, Robin Hood robbed from the

rich for himself rather than the poor, and King John was viewed as a proto-Protestant hero!

To be continued…

|

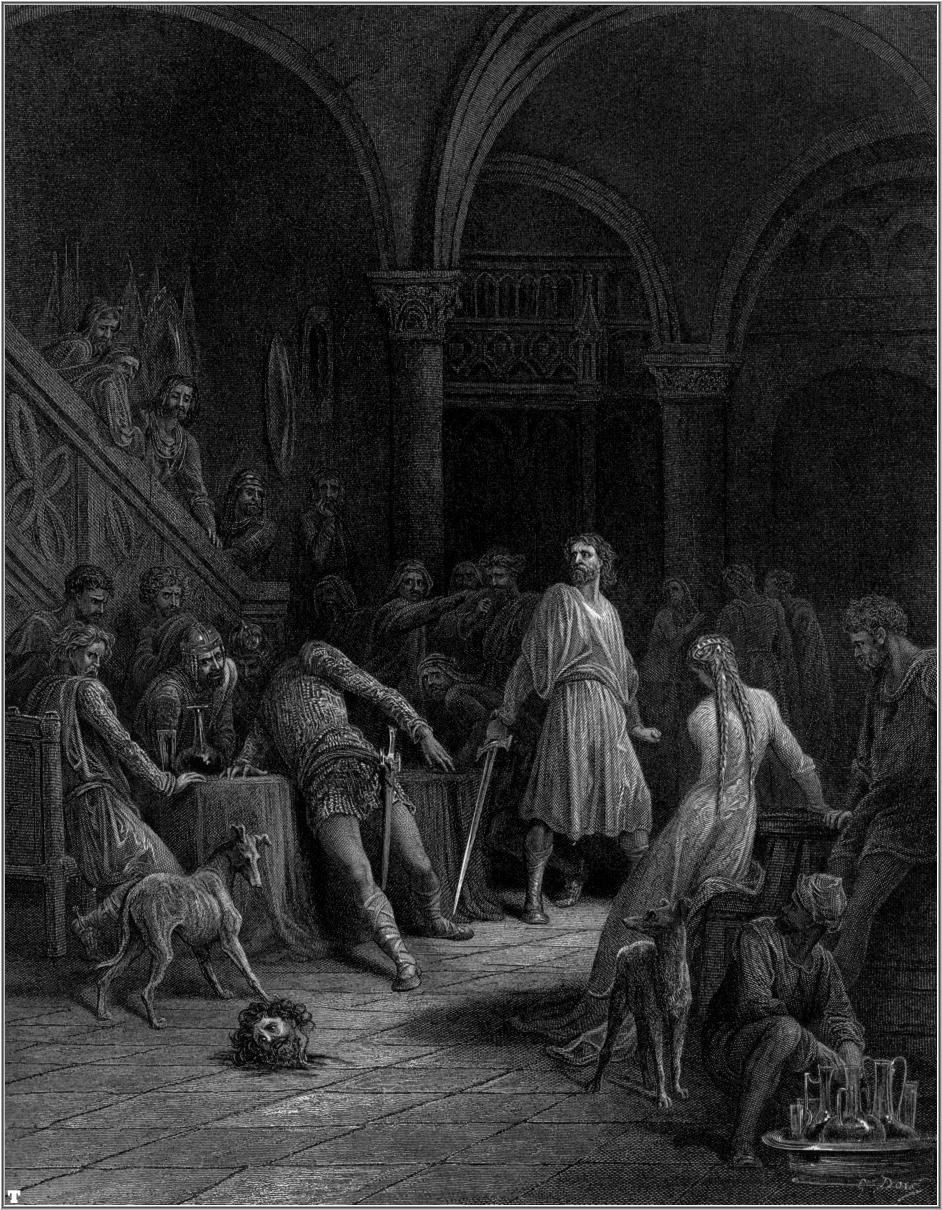

| From Gustave Doré's illustrations of Idylls of the King. |

|

| A scene from Ivanhoe. |

No comments:

Post a Comment