This article is written by request of a good friend (a seminarian) who wanted to read more about church vestments in the Middle Ages.

In truth, my title is misleading because from what little I've gleamed on such an obscure subject, medieval parish churches didn't have vestries (or sacristies); or at least, they were uncommon outside of cathedrals and abbeys. Perhaps the idea to partition a space to hold vestments and vessels didn't seem necessary until the Renaissance. At any rate, without a vestry, a priest dressed for holy rites within the sanctuary, or perhaps his vestments were laid upon a side altar as when a bishop vests.

Why have vestments?

Before we begin, it's worth asking: why should priests or their assistants wear any special kind of clothing in the first place? I've spent a long enough time in the evangelical faith to think a pastor's service dress was a power suit, perhaps also a cross lapel pin. If we to ask your average Catholic in the pew today why a priest wears vestments, I'd bet he wouldn't have really thought about it at all. "That's just the way it's done." It's true, insofar as that a priest is required by liturgical laws to wear vestments.

A more savvy sort of Catholic (the EWTN-watching kind who likes to read apologetic works) might say, "it's to obliterate the priest's personal identity because he acts not a man, but in the person of Christ Himself. The vestments are blessed and set apart for sacred services only, because the Mass is an otherworldly experience." Also not wrong, but that doesn't appear to have been the idea all along. Vestments arose from the street dress of the ancient Church, as fashions evolved but the clergy stubbornly insisted upon wearing the same old styles of clothing for liturgy. This would be like if Christ founded the Church in the 1920's, and a hundred years from now, only priests ever wore neckties and fedoras, but only at Mass, and only in very stylized or "Hollywood" forms.

The medieval liturgist might have said, "our clergy wear vestments because they were handed down to us from the clothing worn by the priests of the Old Testament, who in turn wore them by the express command of God in the law of Moses." This is a tall tale or at least a mistake because ancient Jewish and Christian vestments have only superficial similarities; and by the time the Church made use of vestments (after the end of Roman persecutions and the rise of Constantine, say) Jews and Christians had near zero cultural exchange. Indeed, it was more likely that a Christian would change his habits solely not appear like a Jew, and vice versa.

If we could synthesize all these strains of thought into a greater idea, then, I'd say that a priest wears vestments to: 1.) conform to the rule of the Church (liturgical law), 2.) symbolically erase his own identity by taking up the cloak of Christ, and 3.) emphasize continuity between the religion of the Old Testament and of the New. Each reason may seem questionable on its own, but together, they refute the idea held by cynical nonbelievers that vestments are worn for priests to vainly adorn themselves in rich fabric sewn by the blood, sweat, and tears of a peasant class kept in ignorant darkness by their ecclesiastic overlords. No, friends, it's just the opposite: the priest wears vestments as an act of obedience, to conform himself to the will of God. In theory, at least. This is true for the medieval priest just as much as for the modern one.

The alb

The alb (from the Latin word alba for "white") may not necessarily be the first thing a cleric reached for, but it's the foundation of all the other vestments and must be mentioned before all else. The big white gown evokes all sorts of negative emotions from the modern man: to the skeptic, it ranges from the uniform of fools being baptized in the river after a euphoria of preacher-induced excitement, down to the image of hundreds of robed believers drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid in the anticipation of a better world (even if, at such cult suicides as the one in 1978, no robes were actually involved). Traditional Catholics likewise often deride the alb simply because they see it worn on altar servers, perhaps with ugly sneakers peaking from the bottom, at their local temple of banality (your average Catholic parish) instead of the usual pre-Vatican II practice of wearing a surplice.

In my experience, it's a small matter to say the alb represents purity. It's another thing to stress that an all-white garment in the ancient or medieval world was a challenging thing to make, and even more difficult to maintain. Like teeth in the age before modern dentistry, clothes were most likely to range from shades of yellow to brown. The Roman citizen's toga candida ("bright toga") was only bright white because it was powdered in chalk, in order to draw attention to him while he sought political office; hence he was a candidate for office. Queen Victoria kickstarted the fashion of the white wedding dress, but at that time it was a garment fit for royalty precisely because of its purity, thus any cinematic depictions of medieval peasants or even lesser noblewomen marrying in a white dress are very unlikely.

The alb is also unique in that it's not a vestment for clerics alone, but the uniform of all Christians. Every Christian earns the alb in baptism. I don't know if the Church provided them or if believers had to bring their own, but at least since the time of Saint Augustine, who mentions the custom in a sermon, converts who were baptized on Easter were supposed to wear the albs until the following Sunday. This is why you'll see, in some missals, the Sunday after Easter called Dominica in albis depositis ("the Sunday in which the white is put away").

The alb's form in the Middle Ages was mostly the same as it was in Roman times, from the common tunic worn by men of the old Empire. Lacemaking techniques were very primitive before the Renaissance and unknown in ecclesiastic arts, so don't expect to find any medieval vestments resembling anything like the sheer "liturgerie" of the later centuries. Any decoration was made in the form of embroidery around the cuffs or head opening, or from the 13th century onward, in apparels. The first form, embroidery, can be seen below, dated to the 13th century:

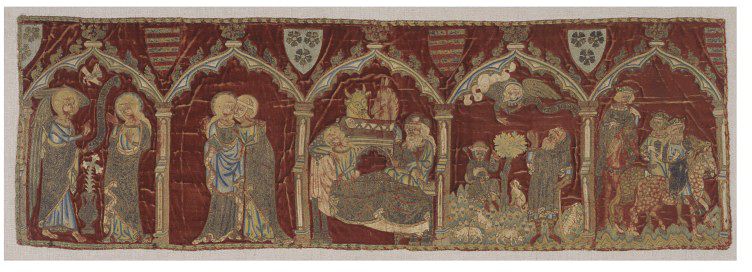

Apparels are strips of fabric that are pinned to the alb's cuffs or the bottom, and can be exchanged with others. This is one very fine example from the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, made between 1320 and 1340:

I can't post an image directly, but this model shows how apparels would be worn on the alb today.

|

| Another apparel is shown on the back of this alb. |

The amice

The amice (from the Latin amictus for "covering" or "dressing") is a rectangular cloth that the priest and his ministers put on before anything else. The idea is to completely cover any sign of the priest's street clothes, including the Roman collar; again, fitting with the idea of obliterating the priest's identity. But since medieval clergy didn't wear anything resembling collars as we know them today, the question of where the amice came from is trickier. A pre-Vatican II rubric had the priest wrap the amice around his head for a moment before pulling it back over the shoulders. The prayer he had to recite while putting it on called the amice "the helmet of salvation". Was this some vestige of when clerics used them as a hood to protect their ears against the cold, like the white hood you might see on a portrait of Dante? But again in the old rites, when a subdeacon was ordained, the bishop would say, "Receive the amice, by which is signified the discipline of the voice". Was it supposed to protect the throat? The Catholic Encyclopedia presents a whole host of theories:

"Early liturgical writers, such, e.g. as Rabanus Maurus, were inclined to regard the amice as derived from the ephod of the Jewish priesthood, but modern authorities are unanimous in rejecting this theory. They trace the origin of the amice to some utilitarian purpose, though there is considerable difference of opinion whether it was in the beginning a neck cloth introduced for reasons of seemliness, to hide the bare throat; or again a kerchief which protected the richer vestment from the perspiration so apt in southern climates to stream from the face and neck, or perhaps a winter muffler protecting the throat of those who, in the interests of church music, had to take care of their voices. Something may be said in favour of each of these views, but no certain conclusion seems to be possible (see Braun, Die priesterlichen Gewänder, p. 5). The variant names, humerale (i.e. "shoulder cloth", Germ. Schultertuch), superhumerale anagologium, etc., by which it was known in early times do not help us much in tracing, its history."

We can take that as a sign that the Encyclopedia had no idea precisely where the amice came from, either, though the medieval belief that the vestment came from Old Testament times resurges once again. My own bet is that the amice protected the alb and other vestments from getting stained by sweat, and was a lot easier to launder. Anyone with experience in laundering vestments could probably back me up. Nonetheless, by the ninth century, it was considered an essential garment for the liturgy.

The medieval amice was the same as it is today, except that it, like the alb, was frequently apparelled. I was unable to find pictures of surviving examples from the era, but here are some reconstructed forms today:

All these representations admittedly look silly until you see the apparelled amice in its final form, pulled back over the chasuble. Then it looks quite splendid.

The cincture

The cincture (from the Latin word cingulum for "girdle", also often just called a girdle) is a cord with knotted or tassled ends that the minister uses to keep his alb and stole together. Over time this has come to represent chastity, but cinctures were probably used from very early times onward for no other reason than to keep the priest from stepping on and tripping over his own alb. All medievals wore belts over their long tunics or dresses for the same reason.

The stole

The stole (from the Latin word stola for "garment", as in the Roman woman's counterpart to the toga) is the sash that deacons, priests, and bishops wear as a sign of their authority. Outside of the strictly liturgical context, even most Catholic priests today will put on the stole during confession to represent their authority to absolve sin. In older times, there was also the concept of a "preaching stole" for priests who gave sermons outside of Mass, or for priests at Mass who were visiting or simply attending in choir. Since it's hard enough these days for priests to get people to come even to Sunday Mass, and since visiting priests now pretty much always concelebrate rather than attend in choir (and thus are already wearing a stole under the chasuble), the idea of a "preaching stole" has now vanished from the Church. Ironically, it may live on in Protestant denominations which formerly condemned the stole as vain popery, but now see it as a useful symbol.

Deacons wear the stole diagonally across the chest. It seems that in the earlier Middle Ages, deacons wore the stole over the dalmatic, as Eastern deacons do today. From the later Middle Ages until Vatican II, priests wore the stole with the ends crossed one over the other. At other times, they wore it with the ends hanging straight down, as bishops do.

The stole seems to have been used in Rome since the sixth century, possibly earlier. Even then, it was conferred upon someone to show that he had entered the ranks of the clergy. In many places, particularly the Frankish lands, priests were supposed to wear the stole not just in the liturgy, but as part of daily dress (that may be why in the movie Becket, you see Thomas wearing the stole even over his usual robes). Indeed, it was the Franks who gave the stole its current name. Before, it was called the orarium, and the Eastern clergy know their form of it as the orarion even today. Later on, some medievals stated that it had a common origin with the Jewish prayer shawl, but as with other theories relating to vestments' origins in Judaism, this one isn't true, either.

Returning to Becket, we're very fortunate to have some of the saint's own vestments preserved at the cathedral of Sens, France. You can see how the stoles from his age were very long, narrow, and generally of uniform width except for a little widening out at the ends. No medieval stoles ever fattened out like spades at the ends as Rococo stoles do, however.

|

| The photo also shows an alb with apparels as I described before, a maniple, and a conical chasuble which I'll bring up again in a bit. Photo courtesy of Genevra Kornbluth. |

The maniple

The maniple (from the Latin word manipulum for "handful" or "bundle") is a strip of fabric, often made out of the same material as the stole, that hangs over the cleric's left forearm. This one will be strange to anyone not familiar with the traditional Latin Mass, because it's hardly ever seen outside of that context. After Vatican II, the maniple was no longer required by the rubrics for Mass, and with no practical purpose to justify it, that meant it was as good as abolished for the post-conciliar Church.

Saint Alphonsus Liguori, in language typical of the 18th century pious, wrote:

"It is well known that the maniple was introduced for the purpose of wiping away the tears of devotion that flowed from the eyes of the priest; for in former times priests wept continually during the celebration of Mass."

I'm not so sure about that. The maniple was also referred to as the sudarium, which literally means a sweat cloth. The liturgical maniple, then, probably descended from ornamental handkerchiefs that upper-class people in Roman times used to wipe off their sweat. Before it took its current form as a strip of cloth around the forearm, it was folded and carried in-hand. One can easily imagine Cassius, the fat games announcer from Gladiator, using it to wipe his brow in between bouts.

The oldest surviving example I know, the maniple of Saint Cuthbert on display at Durham Cathedral, is of the folded handkerchief kind. Predatng the Norman Conquest, it was a gift from Queen Aethelflaed to the bishop of Winchester.

|

| The world's finest sweat rag ever made depicts Saint Sixtus II. I'm not sure how Sixtus feels about that. |

|

| A 14th century German maniple at the Victoria & Albert Museum. By this time, the maniple has been worn as a band around the forearm. |

Considering the maniple's aristocratic origins, I can see why the maniple, which in its earliest days was used even by acolytes, gradually became restricted to subdeacons and higher. What I still don't know is how the maniple came to be used strictly for Mass and no other liturgical function.

The tunicle and dalmatic

The tunicle (from the Latin word tunicula for "little tunic") and the dalmatic (literally "Dalmatian", as in a robe made of Dalmatian wool) are the outer vestments for the subdeacon and deacon respectively. I group them together because in traditional Latin Mass communities today, they're basically interchangeable garments. This is because the medievals wanted the subdeacon and deacon to appear more symmetrical when assisting the priest. In theory, the subdeacon's tunicle is supposed to appear shorter and plainer, but I can't say I've ever seen any meaningful distinction in practice.

The tunicle, in Roman times, was a fine gown to be worn around the villa like a lounge suit. Subdeacons were already wearing tunicles by the time of Pope Gregory the Great, who wrote in a letter that he abolished the custom and had them wearing chasubles as before. (For those of you who are really in-the-know, you may remember that subdeacons and deacons wore folded chasubles during Advent and Lent until 1960. Perhaps this was an attempt to honor Gregory's rule halfway.) But that likewise was overturned, and subdeacons were wearing tunicles again until Vatican II, when the order was abolished entirely.

The dalmatic likewise was a garment worn by the late Roman aristocracy, only even more richly adorned. Deacons began wearing them in Rome as an honorific at the time of Pope Sylvester I, who was contemporary to Emperor Constantine. Both the tunicle and the dalmatic have luxurious, festive origins which help to explain why they were put away during the penitential seasons of Advent and Lent, as I mentioned before. The noble connotations remain today in the secular world because the British monarch still wears a dalmatic during the coronation rite.

In the early Middle Ages, dalmatics reached nearly to the floor and were always white. In the succeeding centuries, the length shortened a bit and colors were introduced at the same time that the system of prescribed colors for the chasuble came into play.

| A southern German dalmatic dating to c.1260, part of a set called the Göss Vestments. By this time the sleeves are shorter, but the sides are not yet cut with high slits like the Baroque dalmatics. |

|

| Left: how the dalmatic should look on a person. |

The chasuble

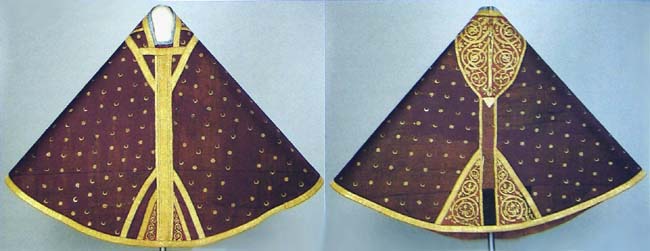

Though this article could go on for nearly twice the length by just talking about copes and episcopal vestments, I'd like to end here with the priest's outer vestment, the chasuble. Called in Latin the casula ("little house"), it descends from a much humbler garment than the tunicle or dalmatic, despite the priest being higher in rank. The chasuble's ancestor in Roman times was a traveling poncho, serving the same purpose as the modern trenchcoat. The chasuble "housed" its wearer completely because the fabric extended from the neck all the way down to the ankle in the shape of a cone; in other words, basically a cope that's sewn shut in the middle.

Many details about the chasuble's evolution can be found elsewhere in plenty, so it suffices to say here that the medieval chasuble was very bulky, encumbering vestment that virtually required the deacon's and subdeacon's assistance to help the priest move around. This is why in the Latin Mass, the deacon and subdeacon are required to hold up the edges of the priest's chasuble when he ascends the altar steps, moves from side to side while incensing, or when he elevates the Eucharist. Without their help in lifting the material, it would have very difficult, if not impossible, for an elderly priest to elevate the Chalice without making an unholy mess.

All these inconveniences caused liturgical "fashion" to cut down the chasuble's length, inch by inch, until eventually, in the 18th century, we were left with the absurdity known as the fiddleback. Such chasubles are like the sleeveless t-shirt, or perhaps the g-string of vestments, and makes the gesture of the deacon pinching the sides of the priest's chasuble pointless, if not ridiculous. That is not to say that a priest's chasuble must be of the full conical form, but the vestment should at least be long and voluminous enough to suggest nobility, dignity, gravitas. The Gothic style attempts to do that while still allowing the priest some mobility. The fiddleback style does none.

|

| The Wolfgangskasel (chasuble of Saint Wolfgang) dates c.1050. It's currently displayed in Regensburg. One of the oldest surviving chasubles out there, but much of the fabric is also reconstructed. |

|

| The chasuble of Bishop Bernulf, c.1150. |

|

| Another view of Saint Thomas Becket's chasuble at Sens. |

|

| An illustration by Augustus Welby Pugin of chasubles and copes as depicted on real effigies (such as on tombs). These are mostly from the later Middle Ages or the Renaissance. |

Did the average parish have a large selection of colors (white, green, red, black, gold, violet, rose)? If so, was it like now where all elements of liturgical dress were color coordinate i.e. having a complete high mass set for each color? Would the average parish have had most garb in a single color (white or violet) and then have a key garb (chasuble, maybe tunic and dalmatics) in the color of the day? What about textiles--wool, silk, linen?

ReplyDeleteI should have written a section on this. The short answer is that the average medieval parish was poor by our standards (despite the popular perception that the Church was a fabulously wealthy institution; this stereotype is only true for bishops and major monastic foundations). But the typical parish owned, say, two or three sets of vestments: festal, ferial, and maybe one for Requiems and penitential seasons.

DeleteFestal: white, if they could manage it. In the early medieval period, in fact, white seems to be the only color known. If not white, then the church just used whatever was the finest material available, regardless of color. In a way, the Church respects this even today when it allows gold to be substituted for white.

Ferial: green, because it was thought to be halfway between white and black. Perhaps this made more sense according to the dying processes of the age, or that green was an easy color to achieve. But as above, the quality of the fabric was the determining factor, not the color. So if the church's white vestments were older and rattier, they'd be used on ferias over a new green vestment.

Requiems, Advent, Lent: pure black was near impossible to make until the invention of synthetic dyes in the 19th century. Therefore, "black" vestments of the Middle Ages were more like navy blue or violet. Medieval parishes would probably use the same vestment for both Requiems and penitential seasons.

As for textiles, I know that wool was the preferred fabric until the re-establishment of the Silk Road in the High Middle Ages. From that point on, you will see silk or half-silk among the more well-to-do churches.

Our modern system of liturgical colors was gradually implemented through the thirteenth century onward by bishops within their respective sees, but they could vary widely. The Sarum Use had red for Sundays through the year, in addition to what we already use it for now, and also Good Friday. At last, the Missal of Pius V established the current white/green/red/black/etc. scheme. Despite the effects of the Reformation, I'd venture to say that the average parish by the late 16th century was in a much better position to have a full sacristy's worth of vestments than it was in, say, the 1100's. We can thank the increased trade from the Crusades, the commercial revolution and rise of mercantilism, and the plundering of the New World for that.

For more info, this is a good article posted on the website for the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales by Arthur Crumley.

Greetings. (Finally figured out how to get a message to you!)

ReplyDeleteYou are welcome to use my photos in non-commercial postings (as above, vestments of Becket). I do, however, require that you attribute them to me and link back to my site. See http://www.kornbluthphoto.com/usage.html where I state:

All photographs © Genevra Kornbluth.

If you wish to use any on your own non-commercial web site, please include one of the following links:

www.KornbluthPhoto.com

or

www.KornbluthPhoto.com/archive-1.html

regards,

GK

Of course. I added a link under the photo in question now.

DeleteCan you help me identify the provenance of the first (black and white) image? I'd like to use it in a book but want to make sure I don't violate copyright. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteCan you help me identify the provenance of the first (black and white) image? I'd like to use it in a book but want to make sure I don't violate copyright. Thanks!

ReplyDelete"Perhaps the gentlemen in the Vatican thought 'LOL, where's the lace?'"

ReplyDeletePerhaps the Vatican was pillaged in 1527 by some Germans, stealing and sacking and sacrileging so that this is the only medieval dalmatic that the Vatican had. Only perhaps, though.

Don't forget the Napoleonic troops who melted earlier papal tiaras. They could have probably have gotten some vestments too.

DeleteI did read somewhere that the church without a sacristy would at least have a chest to store the vestments. It is possible that the celebrant vests at the sanctuary or at a side altar.

ReplyDeleteI saw in the documentary about Father Quintin Montgomery-Wright of Le Chamblac in Normandy (who follows medieval Norman praxis as much as possible than standard Roman praxis in the celebration of the 1962 Missal) that he and his companion Christian prepares a side altar where he vests for Mass.

I think that if I were to be parish priest, I would like to be as eccentric and as medieval as Fr. Quintin, although I would stick to standard practice and be medieval in other details.